Many of the quintessential dining halls scenes — students shouting at each other from across the table, trying to hold a conversation over the deafening din of the Ross dinner rush, sitting elbow to elbow on the floor around the perimeter of Atwater, watching the lunch line stretch out the door at lunch, peering down from the Proctor balcony to point out a crush — have been replaced with a conspicuous emptiness in today’s age of physical distancing requirements.

The three dining halls have historically served as social nexuses and vital centers for the formation of Middlebury as a community. But even as reduced capacities limit how much students can gather, the food we eat — whether perched precariously on a high stool in Atwater, sitting on the Gifford Amphitheater steps outside Proc or tucked in our own dorm rooms — continues to tie us together.

The Campus spoke to Atwater Commons Chef Ian Martin and Ross Commons Chef Christopher Laframboise about how the dining halls function and how they view their roles as cornerstones of the campus community. Martin has worked in the college kitchens for 26 years and Laframboise began working here while he was in high school, 36 years ago.

Shifting tastes

Both Martin and Laframboise have noticed shifts in students' tastes over their long tenures. Students are leaning more towards healthy, fresh food over processed alternatives. Vegans were a rarity 20 years ago, and Martin met a person with a gluten intolerance for the first time 23 years ago.

When Freeman International Center was Freeman Dining Hall years ago, many students made a beeline for the station where they served burgers and fries every single day. Before the pandemic, Atwater only offered one meat entree per meal and had many more vegan and vegetarian options.

“In the last quarter century, many more young people are more aware of what they're eating, and more conscious of the impact of what they eat on everything else,” Martin said.

Still, some things have stayed the same.

“You still have times that you may run out of something, and you throw chicken nuggets on, and you can’t keep up at that point,” Laframboise said.

Martin encouraged students to take the health food craze in moderation and enjoy the freedom of being young to eat whatever they want, though he does think students should at least eat something green every meal.

“There's some kids that come through, they get one burger, two burgers, that's all they want,” Martin said. “Like, what about vegetables? What about your mother?”

Some of the most popular meals right now are Thanksgiving and chicken parmesan, according to the two chefs. While it’s not on their current rotation, breakfast-for-dinner is normally a fan favorite.

Martin loved to watch students “hunt and gather” for their meals, deftly mixing ingredients from the salad bar, lunch offerings and other items from around the dining hall, using the microwave or grilling on the panini press to come up with masterful new creations. With many of the microwaves and other amenities — such as a full salad bar — currently unavailable due to health and safety precautions, he misses witnessing students’ innovation and is eagerly looking forward to when that can return.

Fostering connection

Though they have remained in their positions through many generations of students, Laframboise and Martin still feel closely connected and treasure the bonds they have formed with students.

“The dining halls are really important to student life,” Laframboise said. “It’s our role to facilitate that [connection] and to make good food to keep the students happy.”

Laframboise makes a point of trying to meet and help out first-year students. At meals during orientation, Laframboise looks out for students who seem lost or confused. He will often approach them, strike up a conversation and try to help them through whatever is troubling them.

Both Martin and Laframboise said they have developed relationships with students who seek them out, particularly those with dietary restrictions who need special meals or accommodations. They have also formed particularly close relationships with students who work in the dining halls, some of whom have told Martin that working there was one of their favorite parts of going to Middlebury.

Some of the most gratifying relationships are with kids who have worked with us over the years,” Martin said. “We’ve had some really great kids.”

Laframboise described the kitchen as “a family”; staff support each other on busy days, play practical jokes, poke fun at each other and get under each other’s skin — just like any other family. Many cooks come to view the dining halls as their own campus home and feel a real attachment and pride.

“I certainly feel privileged and lucky to have the staff that I have,” said Martin.

Making the menu

Normally, each dining hall functions more or less as an island unto itself, using its own recipes on its own five-week rotation and only occasionally coordinating with the other dining halls for popular meals like chicken parmesan. This year, to even out demand and reduce crowding, the dining halls are running on the same, pared-down, three-week cycle.

Though the servery is normally buffet style, dining staff have been serving food to students this year to reduce the number of people touching utensils. This has drastically increased the workload of a reduced staff team, making it impossible to cook large numbers of complex dishes each night. The dining halls have had to pare down their menus to expedite the serving process and make sure lines don’t get out of control.

The weekend Chef’s Choice brunches remain an outlet for innovation, even as processes become more standardized. Chefs examine what ingredients or dishes are left over for the week and whip up something new. If the dishes are successful, they are sometimes incorporated into the regular rotation.

Chef’s Choice is also a good opportunity to pilot new meals. Occasionally, one of the cooks will see a recipe online or enjoy a dish at a restaurant and want to try their hand at making it for the student body. Brunch, where the meal counts are low and there are more options, is a great chance to see if meals are a success.

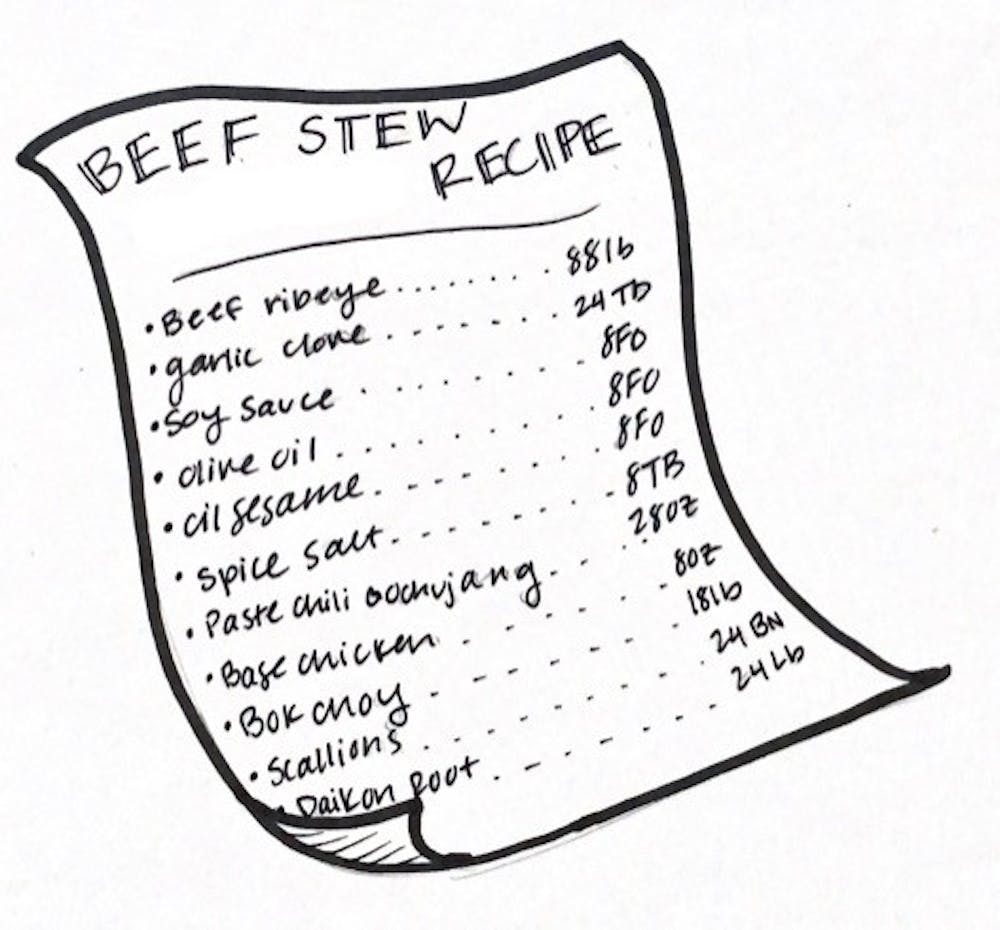

Other recipes — like one of Martin’s favorites, pork griot — come from students submitting recipes from home. Laframboise loves recipes from home and enjoys the puzzle of figuring out how to adapt them to the needs and portions of the school as well as connecting with and learning about students through their requests.

Looking forward

Neither Martin nor Laframboise are certain what the future will hold. Without the normal schedule of finals week, senior week and commencement, Martin can’t rely on past experience to plan how much to cook in the next two weeks. And no one knows for sure what the fall will look like, though the college has thus far painted an optimistic picture of a return to mostly normal operations.

“This year has just been kind of rough. We've never had a year like this, so it makes it very stressful for us sometimes,” Laframboise said. “Hopefully, we're back to normal [next year] because that would just relieve a lot of pressure off everyone, students and staff.”

Sophia McDermott-Hughes ’23.5 (they/them) is an editor at large.

They previously served as a news editor and senior news writer.

McDermott-Hughes is a joint Arabic and anthropology and Arabic major.

Over the summer, they worked as a general assignment reporter at Morocco World News, the main English-language paper in Morocco.

In the summer of 2021 they reported for statewide digital newspaper VTDigger, focusing on issues relating to migrant workers and immigration.

In 2018 and 2019, McDermott-Hughes worked as a reporter on the Since Parkland Project, a partnership with the Trace and the Miami Herald, which chronicled the lives of the more than 1,200 children killed by gun violence in the United States in the year since the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Florida.