For me, the solar panels mark the threshold between the campus and the Knoll, Middlebury’s organic farm. It’s the toll gate cutting off the retreat from the midterm craze. I walk past the dark, orderly panels and set my mind off of academics for the next few hours.

During harvest season, you can smell the farm before you see it. After a night of rain, it had a gentle mix of grass, dirt and honey that rose out of the earth with the morning sun. It was hawk migration season –– the birds circled overhead, smoothly, under a cloud-filled sky.

Looking out of a window in the pizza oven shed.

The farm was quiet on a Friday morning when Megan Brakeley’06, the food and garden educator at the farm, stepped out from her car and greeted me. She was wearing a faded pink jacket with hearts sewn into the front pocket and jeans patched up at the knees.

I was struck by her laughter and the joy it carried — Megan spends more time laughing than not. Almost immediately, she appeared to me as someone who is not merely content but sincerely happy and grateful with where she’s found herself in life.

Megan pre-heating the pizza oven.

Megan started working almost immediately and did not stop until sunset. She picked up a beer can from the ground and scraped off the leftover ashes from the pizza oven. There is a baking event in the afternoon, so the oven must be preheated two hours prior.

“It’s amazing how much we can do here without running water or electricity,” she said, opening the side windows, which are counterbalanced by a few weights tied together.

Megan and Anna, a fellow photojournalist from the Campus, opening the window of the pizza shed.

Megan moving buckets of beans out of the main shed.

The farm started with the vision of two students who wanted a place open enough to the campus to be accessible by foot but far enough to feel like a retreat. In 2003, with the help of garden educator Jay Leshinsky, who still works at the Knoll, Bennett Konesni ’04.5 and Jean Hamilton ’04.5 started building the shed, the solar panels and the well.

“Back when they were envisioning this farm, I had some connection and access to college funds,” Jay said. “So, I did what I could to help.” Now, almost ten years later, Jay still volunteers regularly at the farm, helping with gardening tasks as well as running classes there.

When I first met him, he pointed to a huge Algonquin Long Pie Squash and winked. “The one that got away,” he said.

The overgrown Algonquin Long Pie Squash.

Megan grew up between Alabama, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. She graduated from Middlebury with a major in Spanish and a minor in environmental studies. Although she never anticipated returning to the college after graduation, Megan found her way back after meeting her spouse, who lives in the town of Middlebury.

“There is a gravity at Middlebury that brings people back,” she said. “Traditional farming in the U.S. has a very on-the-grind, go-hard culture. It can be very stressful and I wasn’t sure if that’s what I wanted. But I love my job [at the Knoll]. Every time I come to work, I am amazed that I get to do this.”

The main shed.

Gardening and building tools from the main shed.

Megan currently lives in town with her husband and two children and is very grateful for being able to have a home in Middlebury. She said she would not have been able to afford a home here if not for the fact that her spouse’s family lived their whole lives here and have local connections. The already expensive market in Middlebury was made worse by the severe housing shortage during Covid-19.

“It is very hard to get your foot into Middlebury, whether it’s the town or the college,” Megan said. “We are very lucky. You hear students complain about living in Marriott, or Bread Loaf. I think there is a real… disconnect here [between the student and the local population].”

After firing up the pizza oven, we met up with Jeannie Bartlett ’15, who was leading an experiment on carrots with a group of students. The activity was a part of an environmental studies course.

The group watched Megan demonstrate how to dig out a carrot. “It’s as much about the soil as it is about the carrot,” she said. “I think about it as asking the carrot for permission to extract it. If it’s not willing to come out, listen to it and don’t force it, or you will break it.”

Megan demonstrating gardening techniques to the class.

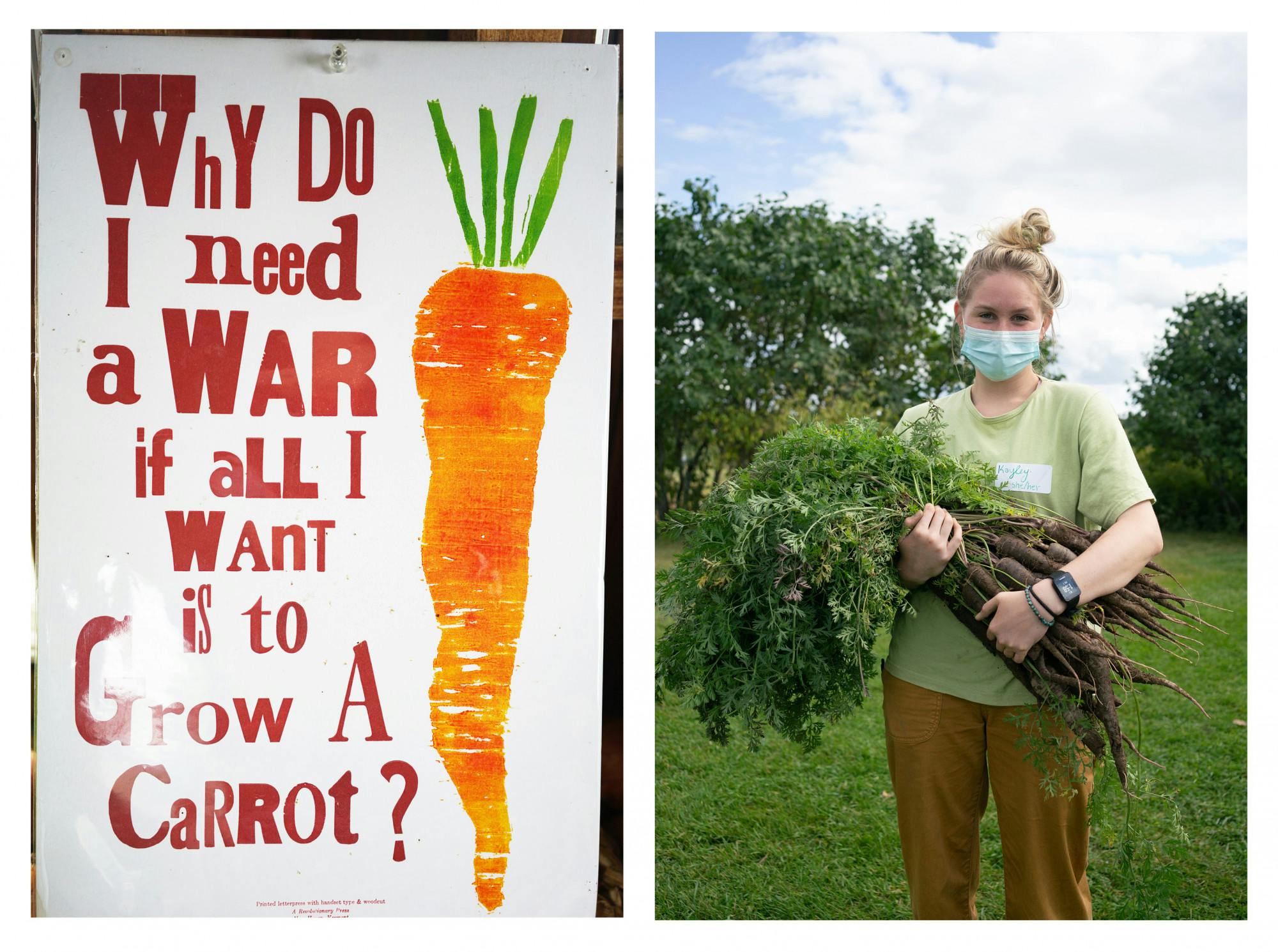

Left: a poster from the main shed. Right: students digging out carrots for their experiment.

The group spaced themselves and extracted orange and purple carrots from the earth. They are then categorized into first and second grade, with first grade being the more commercially desirable products that will go straight to the market.

Back at the oven, we chopped up the carrots and roasted them with honey. The purple carrots tasted like a mixture of carrots and sweet potatoes. Compared to the orange ones, the purple carrots have more variation and forking, along with a different nutrition profile.

In the afternoon, Chief Don Stevens of the Nulhegan band of the Coosuk Abenaki nation visited to share his wisdom on agriculture and food. The Chief has visited and maintained a sustained relationship with the farm since 2019. Before the event, he sang a calling-in song and played the frame drum, which is used to release spirits for guardianship and guidance.

We shucked beans as he told us stories of the “Corn Mother.” The farm was quiet except for the sound of beans falling in plastic buckets and Chief Stevens’ booming voice between the rustling crops.

Chief Stevens showing the drum and Knoll intern Andrea preparing food for the group.

Corn before and after the corn mill.

According to the “Corn Mother” story, the first mother had to watch her children go hungry daily as food was scarce and they sustained themselves through a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. Finally, unable to bear watching her children go hungry anymore, the mother decided to go to the Creator and offered her life in exchange for food. The Creator accepted, and she was transformed into corn, the crop that still feeds her children today.

“We are all related, including these beans,” said Chief Stevens. “Some people say well then you are eating your relatives, but didn’t you feed from your mother’s breasts? Isn’t the Earth mother also a mother? Our ancestors made themselves into food to feed us. That is why I have a deep respect for the thousands of people before me that passed [the seeds] on to feed me, and I will pass it on so it can feed people after me.”

These stories connect ancestral lineage with the land and the food. To eat is to be intertwined physically with the land, and to till the land is to pass on the lineage and custody to your children.

The peeled skunk beans.

As the sun began to make its way towards distant hills, Knoll interns Andrés, Isabela and Tashi prepared the pizzas, and a student band arrived to play their guitars by the firepit. The sky was once again a mixture of purple-ish pink and blue characteristic of Middlebury’s sunsets and in the distance, a few figures were making their way over for evening events or finishing up their afternoon run.

The pizza oven.

Sitting across from me, Megan compared the farm on which the students harvest, garden or relax to a “palimpsest,” a manuscript from which the original writings are erased to make room for later ones but whose effaced print nevertheless remains in traces. At times, our individual efforts and traces also remain with the land and thread us together to people that came before us and those who will come after.

“The farm sites the students to the land, and all the history and relations that come with it,” Megan said. She picked several flowers from the garden for her friend and offered one to me.

Window of the main shed.

Florence Wu '22 is the multimedia editor specializing in photojournalism. She enjoys photography as a way of connecting with others, as well as recording special events and moments in her personal life. She is inspired by the works of Robert Frank, Joel Sternfeld, Alec Soth, Teju Cole, and Gregory Halpern. This year, she will be working on a photojournalism project on the lives of workers at the college and town of Middlebury. Feel free to contact her via email for photo, video or podcast ideas.