The Hirschfield International Film Series’ most recent feature “Drive My Car” is not unlike a long road trip. Road trips usually elicit two seemingly conflicting feelings: boredom and awe. With a runtime just shy of three hours, director Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s lauded masterpiece could easily miss the mark if his audience fails to stay engaged. The second feeling takes more work. Like a road trip with changing, beautiful scenery, motifs come and go throughout the film’s duration. However, the theme of multicultural understanding between the different Asian cultures represented ties the whole film together and leaves the audience with a profound sense of awe.

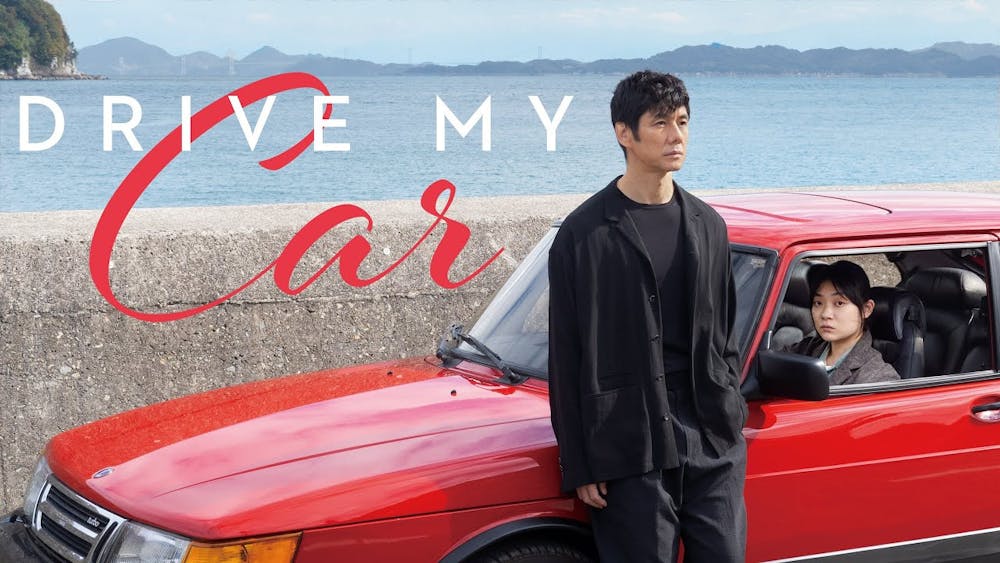

The film centers around actor and director Yusuke Kafuku (Hidetoshi Nishijima) and his wife Oto (Reika Kirishima), a screenwriter, who both live in Japan. When Oto dies suddenly, Yusuke cannot continue acting in the play in which he is currently cast. Two years later, he settles for a job in Hiroshima directing the same play but with a twist; he adds Korean sign language to the list of foreign languages used in the play. Throughout the second half of the film, the multilingual cast are frustrated by Yusuke’s directing as he guides them through his vision with suboptimal communication.

“Drive My Car” pushes the audience’s expectations of dialogue, challenging them to focus on active listening. The cast, and even the directors, cannot fully communicate with each other. Yoon-A (Park Yu-rim), a mute actress who delivers her lines using Korean Sign Language (KSL), is the key figure in this theme of listening. In one of the most heartfelt scenes, where Yusuke and Misaki (Tôko Miura) are invited to Yoon-A’s home for dinner, she reveals that — while all of the other cast members are frustrated with the rehearsal process — she is greatly enjoying being able to listen and understand the other characters through their non-verbal communication.

The end of the film shows the final scene of the play, where Yoon-A’s character is philosophizing the meaning of life over the shoulders of Yusuke while he sits and sheds a tear. Here, it is obvious that the two characters are deeply connected, though they do not speak the same language. They both look forward to the play’s audience, and in many ways, viewers embody the role of the play’s audience.

The use of subtitles is extremely important to this play, and can make or break the experience. There are no subtitles for the English, and the Japanese and Korean are demarcated with parenthesis. Some lines are not translated at all. These elements can be a bit distracting, and even take away from the message that understanding can surpass translation. It is a bit hard to watch the last scene, where the English translation of Yoon-A’s character’s philosophy of happiness is not particularly poetic or well-worded. This can entirely ruin an audience member’s feeling of immersion in the film.

Many of the hand motions in KSL are repeated throughout the film. I, personally, got the gist of at least five important words just with context clues. It could have been interesting and more potent for the final act of the play, after three long scenes where KSL is used, to maybe even cut back some of the subtitling. This would arguably drive the message home even further, that one who truly listens does not need translation; this idea is weakened with the at-times distracting presence of said subtitles.

Another part of the movie that might take the audience out of the film was two controversial plot elements that went largely underdeveloped. The first choice was to portray adultery as morally gray. Early in the film, Yusuke sees his wife cheating on him with fellow actor Takatsuki (Toshiaki Inomata) — among other men — and seems strangely ambivalent. In an emotionally charged scene at the end of the film, he accepts the premise that Oto could have loved him fully and still have cheated on him. Although he feels empowered to express his anger at her for the first time since her death, he seems to accept this reasoning.

The second point of tension, and arguably more controversial, is with the same actor Takasuki’s other moral failings. Not only did he sleep with his boss Yusuke’s wife, he also had sexual relations with a minor and beat someone to death. Both of these points are glossed over at best and at worst are portrayed in a manner where the audience plausibly feels bad for him. Regarding recent films, especially with “Licorice Pizza’s” 10-year age gap and the famously controversial relationship in “Call Me By Your Name”, there has been outrage and downright confusion at why these taboo relationships are not only ignored in some cases, but glorified in others.

“Drive My Car” has so much to offer, and, while hard to digest in one sitting, could leave the audience either bored (and perhaps morally outraged) or utterly inspired.