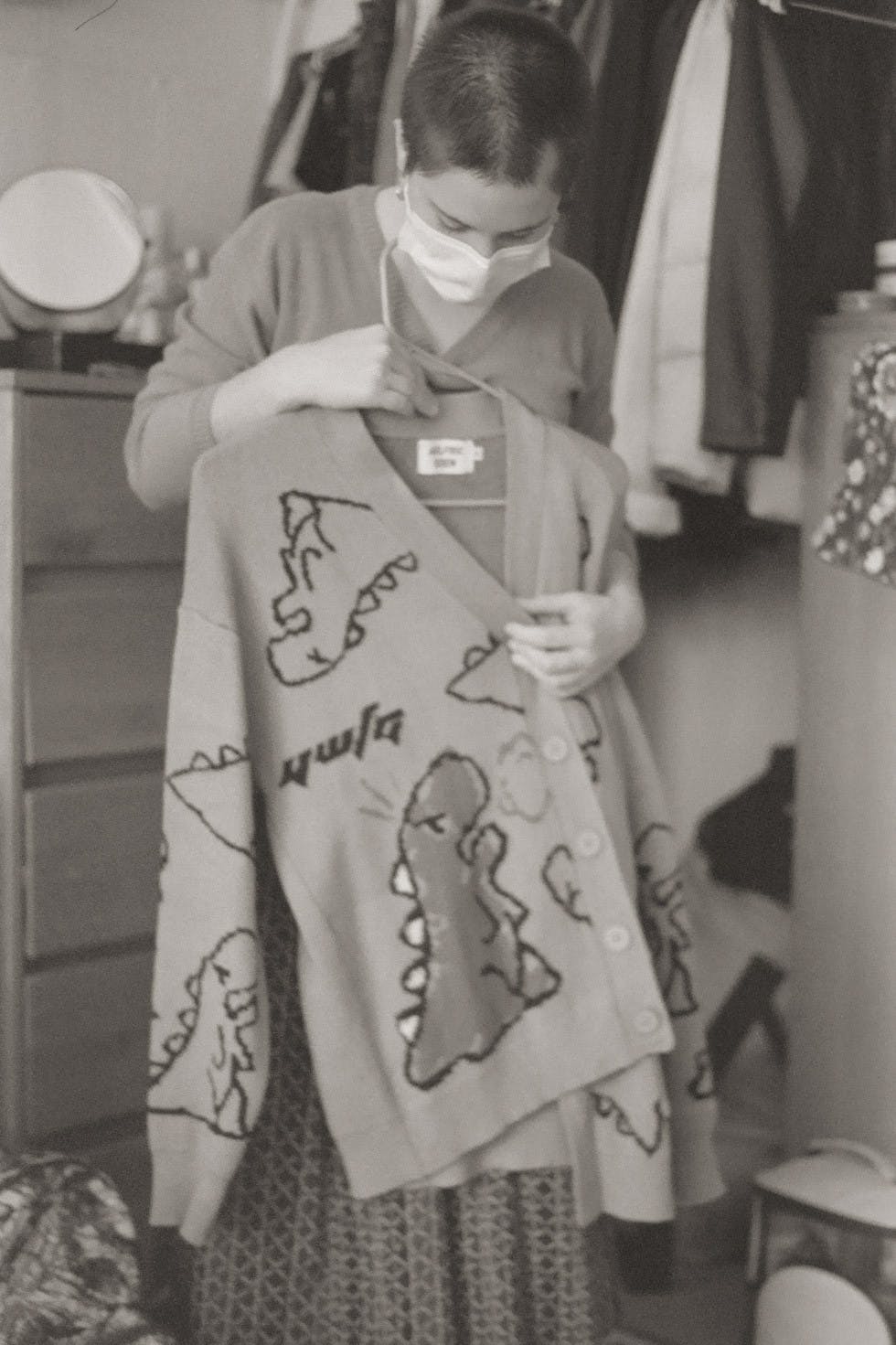

Over the course of my life, I have met people with various kinds of collectibles: soviet era pins, baseball caps, and shark teeth. Meeting Summer Eaton ’25 (they/them), I was introduced to their avid dinosaur collecting. On the shoe rack underneath their lofted bed were rows of dinosaur print footwear including Crocs and Converse. They also have a dinosaur sweater and t-rex necklace gifted by their mother at graduation. Back in their hometown of Hanover, Penn., they own a dinosaur lawn chair and a dinosaur lamp. It was a comprehensive collection.

Summer showing me their dinosaur sweater

“I would say it's an obsession. At first, it was an, ‘Ey! Dinos are cool.’ It spiraled into everything I was getting was dinos. I’m fine with that. My younger siblings also now love dinosaurs,” Eaton explained.

Eaton is comfortable using terminology such as ‘disability’ and ‘neurodivergent’ to describe aspects of their identity. However, it hasn’t always been that way. Since they were diagnosed right after the pandemic, they’ve only recently been able to use a concrete label on a lifelong struggle to how they exist in the world. On top of that, Eaton feels there is cognitive dissonance between the representations of disability in the media and their own lived experiences.

“People look at me and say ‘That's not a disability. Everyone has that sometimes.’ It doesn’t make my choice to do so any less valid. It's really personal how you choose to identify yourself.”

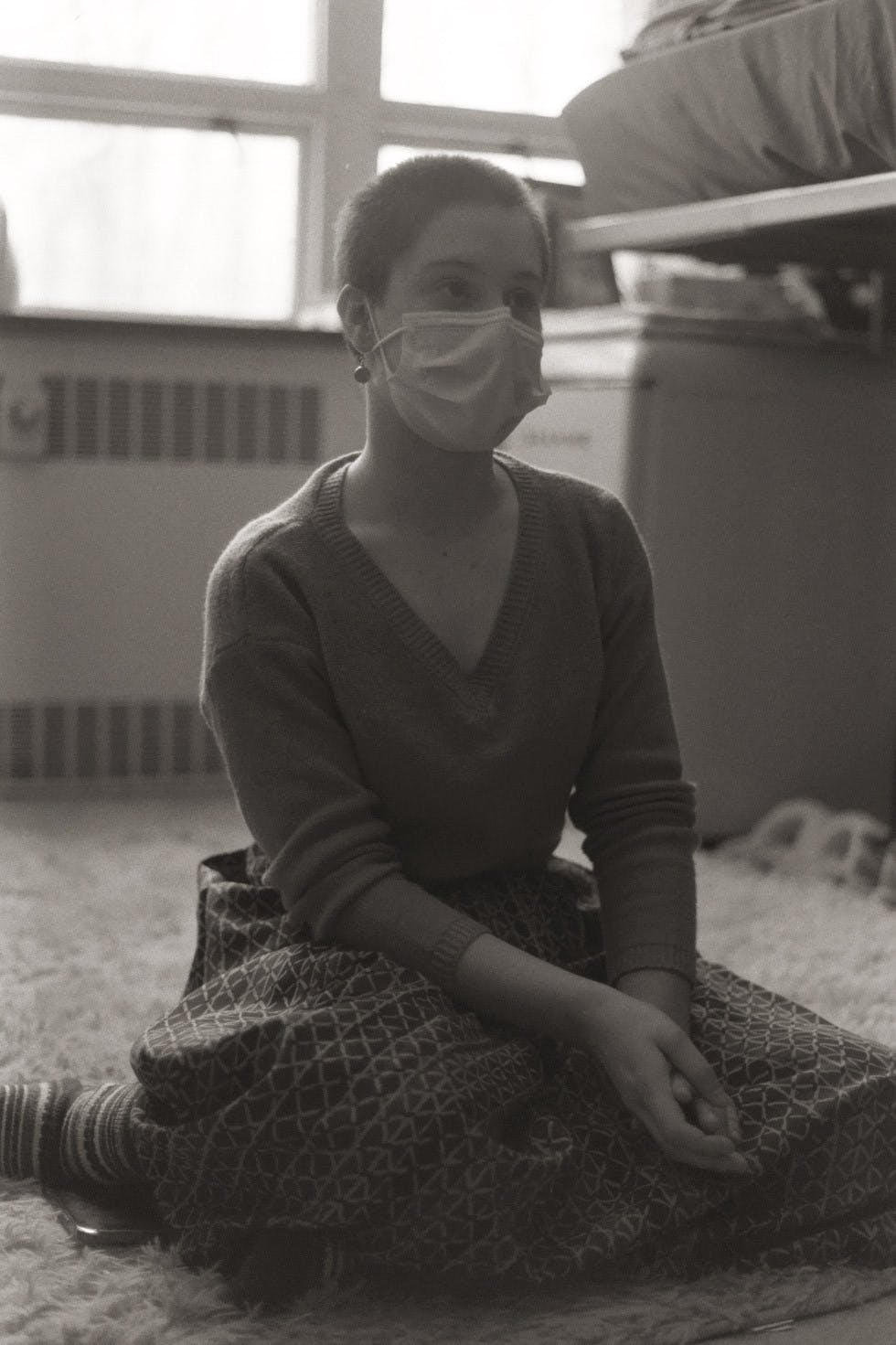

Summer resting on their carpet

Eaton refuses to comply with the expectation that neurodivergent people have to make themselves more palatable to those who are neurotypical in social situations. That said, they feel there is still distance between the way neurotypical and neurodivergent folks approach the process of socialization. “I wish neurotypical people could perceive the amount of effort I put into everyday interactions. Even to have a basic conversation requires so much work in my brain and so much energy,” they described.

“The world is not how they perceive it. The world is not how I perceive it. When I’m in an interaction with someone, I’m thinking, ‘How do they perceive the world? How can I understand the way they perceive the world? How can I understand them as people?’ For the most part, I don’t get that back in return.”

Eaton’s experience with the Disability Resource Center (DRC) has been limited to an email exchange requesting their Letter of Accommodation. They commented that the purposes of the DRC still remain ambiguous to them and for this reason, they do not know how to reach out. Eaton wishes that the DRC took more of an active role in communicating to students with disabilities throughout the year so that the center would feel more accessible.

“I’m having a lot of trouble remembering to drink water. I’m not going to email them in terms of helping me create schedules for eating and drinking, that’s dumb. But it’s not dumb. And I still do need help making schedules and taking care of myself and releasing some of that stigma and saying that a lot of disabled people struggle with the maintenance of taking care of themselves.”

“I can’t play soccer, but I’m so passionate,” Rodrigo Franco ’25 (he/him) passionately tells me as he raves about Palmeiras, his local soccer team. “It’s probably because of my dad. I've been going to soccer games ever since I was a kid.”

Franco grew up in São Paulo, Brazil and speaks several romance languages. Relative to the other languages he speaks, Franco likes the English term “disability.”

“In Brazil, if we were talking about disability, the term is deficiente which means ‘deficient.’ I don't like that term because it's not that you are a deficient human being, rather you are unable to do certain things.”

It’s hard to miss Franco’s easygoing and positive nature when in conversation with him. He views his disability as a matter of self-reflection and acceptance that it is an integral facet of his identity.

“I do not know life without a disability. It's a matter of recognizing that it's a part of me, but it's not all of me,” he said.

Fittingly, Franco also has a love for philosophy and questioning his purpose. He enjoys observing the natural flux of life and constantly reminds himself to be grateful for the people he loves most. While acknowledging that disability can have a positive and negative perception, Franco flows through life as an optimist.

“I try to look at things from the positive side. I've fought really hard to be alive right now. It's a privilege to be here,” he said.

Franco’s experience with the DRC has been positive. “The DRC has been great in welcoming me to Midd,” he said. “They have been doing everything they can to make sure I am as comfortable as I can be.”

However, Franco admits that certain services relating to campus mobility during the winter months should be improved. “I don't know if the DRC has the power to do these things but when it's snowy and icy, having to walk across campus can be challenging. Some universities have a bus system, but we don't. We have to walk. I like to walk, but depending on the conditions it can be difficult.”

As a final note, Franco wanted to mention that he is naturally outspoken and is at ease speaking about his disability with others as it is part of embracing himself. “Sometimes people hesitate to ask me about my disability or bring the subject up,” he said. “Don't hesitate. I'm very comfortable with it.”

Last fall Isabel Linhares ’22.5 (she/they) took two courses with Dr. Susan Burch, the head of the American Studies department, who specifically teaches disability studies. That was enough for Isabel to switch from a Physics and Molecular Biology and Biochemistry double major to pursuing an Independent Scholar major in a field related to disabilities.

“I fell in love with the way that she teaches, how accessible she made her teaching and how relevant the material was to everything I was going through,” Linhares said. “I began to think beyond the western biomedical model of disability.”

Over winter break, Linhares realized that her passion for art therapy could be pursued as a career. “I'm aware of the history of psychiatry and psychology in perpetuating ableism and other systems of oppression. I want to practice art therapy in a way that works with disability justice principles in mind while taking into account that struggles are not individual problems and are instead indicative of larger systemic patterns.”

Linhares is prominently engaged with disability activism on campus. The roots of her disability activism tend to begin with a simple dinner conversation with friends and realizing a shared accessibility need that must be met. With the support of the Concerned Students of Middlebury, Linhares and her friends will advocate for their needs by collectively writing a mass email to a campus resource such as Director of Education for Equity and Inclusion Renee Wells or the DRC. “It's hard to know what is considered activism because every week there's a new fight for a different access need,” Linhares admits.

In the past, Linhares tells me that she and her friends advocated for mobility scooters. After resistance from the DRC, the request was eventually granted. “We identified that we needed help and we weren't going to take no for an answer,” they said. The scooters are also now available to students who are injured.

Isabel mid-speech

According to Linhares, Middlebury’s social scene is particularly exclusive and unsafe for students with disabilities.

“The presumed hyper-abledness that Midd actively tries to foster through our predominantly white, able-bodied, athlete and outdoorsy culture makes a lot of social spaces not compatible and irrelevant to us that cannot fit that label of what Midd culture defines its ideal student to be.”

Finding well-connected disabled folks on campus through classes and non-disability related club events during their first year has been Linhares’ primary means of surviving these dominant spaces.

Isabel sat in their wheelchair

“We’re everywhere. We're all struggling to be in these spaces. It's not too hard to figure out who's also struggling and band together. Once you make those friends it isn't always easy to hang out together if you both have mobility challenges. It’s a challenge but finding that community is how I've gotten through Midd,” she said.

Along with learning from student insights, I wanted to include the perspective of the DRC as well. Over a Zoom call, I chatted with Jodi Litchfield (she/her) and Peter Ploegman (he/him), both ADA coordinators who make up the DRC.

Originally planning to be a high school history teacher after graduating college, Ploegman switched tracks as he began working in higher education when he had to record audiobooks onto cassette tapes. That was his first introduction to the field of disability in the workplace. After that, he became involved in training by the Association on Higher Education and Disability and became a Learning Support Specialist. Ploegman eventually joined the office at Middlebury in January of 2020.

Litchfield is a longtime member. She joined the office in 1999 as an assistant director, four years after the DRC was founded. “I was by myself in the office straight until 2017 when we finally hired a second coordinator because the number of students had expanded so much since the beginning that we definitely needed a second coordinator at the time. We’re grateful we have Peter here,” Litchfield said.

Prior to the DRC, the office was called ‘Student Accessibility Services.’

“The difference between these names is that we’re not a service-oriented office. By changing the name to ‘center’ we are trying to become a part of campus culture and another aspect of diversity on this campus. That’s why we have a seat on the Office of Institutional Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (OIDEI),” Ploegman explained.

Litchfield and Ploegman said that inaccurate statements have been made about the DRC but did not go into further detail during the interview. They both highlighted that they welcome feedback and are open to Middlebury students reaching out to ask questions.

“We encounter students every semester who have overcome some fairly steep challenges to get here. We acknowledge and applaud that. We do our best to provide the accommodations that will give them the best chance to be successful,” Ploegman commented.

As a photojournalist, I acknowledge the historical role the media has played in perpetuating ableism through representations of disability. My primary intent for this piece was to allow each interviewee to have agency over how they wanted to portray themselves. In order to respect the privacy of all individuals, I began each interview by explicitly stating that not all questions had to be answered. Additionally, I offered my camera to each student and allowed them to take a self-portrait. The expressions of these self-portraits have been included throughout the piece. Finally, I would like to emphasize the various ways students with disabilities exist on this campus, and the extent that Middlebury as an institution comes to support us as we actively strive to become a more accessible and inclusive community.