“From the Archives” is an opportunity for various writers to visit the Middlebury Special Collections and write about a different artifact each week. The Special Collections boasts over 10,000 historic items, and through this column we encourage writers to explore not only the college’s history, but also the history of the world around us.

Astronomy news is abuzz. On Sept. 26, Jupiter came the closest it has been to Earth since 1963 — almost sixty years ago. Additionally, the James Webb Space Telescope, launched in December 2021, sent back its first images to Earth in July of this year. Aside from being visually stunning, these groundbreaking photos are also taken in the infrared spectrum, revealing previously unknown information about the universe.

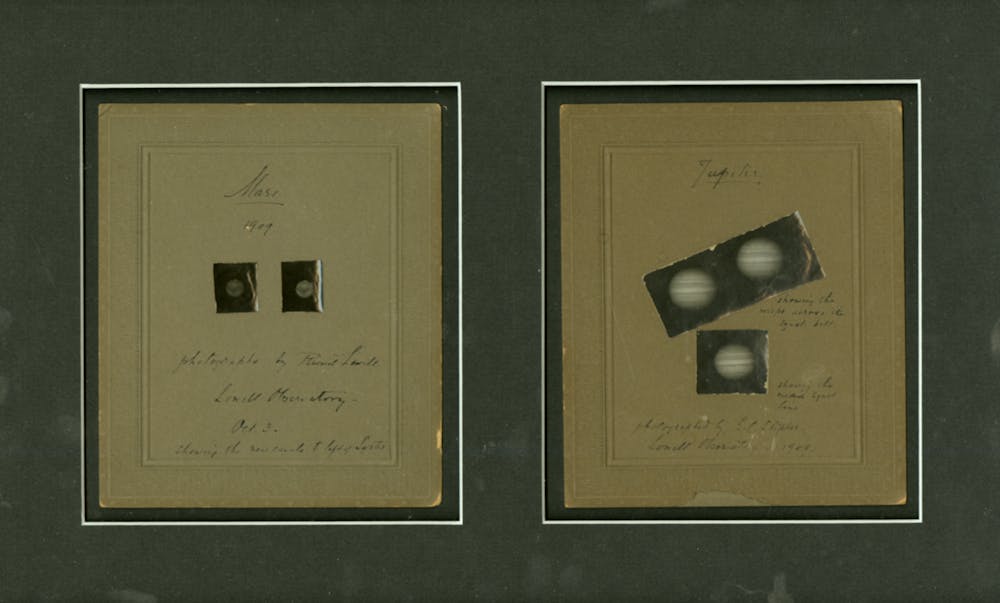

Given these exciting developments, taking a look back at the 1909 photos of Mars and Jupiter in Middlebury’s Special Collection, located in the Davis Family Library, feels particularly timely. Mounted on cardboard in a patterned black frame, they are surprisingly tiny. Each one is only a few centimeters across. They show the two planets against a pitch-black backdrop. Jupiter’s distinctive bands are visible, as are the dark shadows on Mars’ surface.

The Jupiter images were taken by astronomer Earl C. Slipher, and the images of Mars were taken by astronomer Percival Lowell. Lowell once used the Mars images to support his theory of extraterrestrial life. He believed that the shadows on its surface, which have what appear to be geometric outlines, were Martian-made canals transporting water from Mars’ polar regions to its equator. Lowell’s theories influenced author H. G. Wells’ sci-fi book “The War of the Worlds.” Since then, it’s been confirmed that the shadows’ seemingly straight borders are an optical illusion.

Lowell established the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Ariz., the location where the photos were taken using the 24-inch Alvan Clark refractor telescope. The telescope was first used on July 23, 1896. Using the same telescope, astronomer V. M. Slipher made observations about spiral galaxies that provided the first evidence of an expanding universe. It was also used to produce lunar maps and allow astronauts to familiarize themselves with the lunar surface in preparation for the Apollo 11 mission.

The historical ownership of these photos also involves some of Middlebury College’s most decorated faculty. They were originally owned by renowned Professor of Physics Ernest Calvin Bryant ’91 (1867-1942), who went on to found the Physics Department in 1912. His obituary was written by fellow Professor of Physics Benjamin F. Wissler.

“For many years he was voted ‘Middlebury’s most valuable teacher,’” Wissler wrote. “Professor Bryant served longer than any other member of Middlebury’s teaching staff.” At the time, that meant 45 years at the institution.

The images then fell into the hands of Frank Winkler, the Gamaliel Painter Bicentennial Professor Emeritus of Physics. In 2014, the college established a professorship in Winkler’s name, which Professor of Astrophysics Eilat Glikman currently holds.

“Winkler joined the Middlebury faculty in 1969 and has taught nearly every course in the physics curriculum during his 45 years at the College,” according to the announcement of the professorship.

“We’re thrilled that this professorship will honor Frank’s long and distinguished career at Middlebury,” Professor of Physics Noah Graham said in the announcement. “Frank has shaped and guided our department through a period of remarkable progress.”

In 2015, Winkler donated the photos to Special Collections, along with a letter explaining their origins.

Rebekah Irwin, director and curator of Special Collections, said the photos’ record of provenance, or history of ownership, was unknown.

“All we know is the history that Professor Winkler shared with us, and that’s very common with gifts or donations,” Irwin said.

According to Irwin, many Special Collections items are acquired as donations and gifts. She also buys items from rare book dealers and auction houses.

“In many ways it’s similar to the museum,” Irwin said, referring to the Middlebury College Museum of Art in the Mahaney Arts Center.

Some purchases are also made specifically for certain courses.

“Normally we do that in collaboration with professors who are teaching classes,” Irwin said.

The Special Collections team has a special process for storing photographs. The Mars and Jupiter photos were stored in foam inside an acid-free, humidity resistant cardboard box, which Irwin says is standard practice.

“This space, 101 in the library, has its own heating and cooling system,” Irwin said. “We maintain a different temperature and humidity, and we do that because it’s better for paper, filament and photography.”

The space has a special fire suppression system, as sprinklers would damage the archived material, and a safe that is fireproof and bombproof. Motion sensors are in place to prevent potential theft. Special Collections staff also keep a look out for certain bugs that consume paper, which especially threaten rare and antique books.

Irwin pointed out another rare item that is related to the history of astronomy in the library’s collection, a 1653 edition of the book, “Petri Gassendi Institutio Astronomica.”

Written by French astronomer Pierre Gassendi, the book discusses the ideas of Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe and Prussian polymath Nicolaus Copernicus. It also includes Galileo Galilei’s “Sidereus Nuncius,” an astronomical treatise which was highly controversial when first published in 1610, and Johannes Kepler’s “Dioptrice,” an investigation of telescopic lens construction for astronomy, first published in 1611.

Interested readers can learn more about the Special Collections’s acquisitions process and storage protocol, as well as view Gassendi’s treatise and the images of Mars and Jupiter, by scheduling a visit to Davis Family Library 101 where the collections are located.

https://mbury.iii.com/record=b4308665~S2