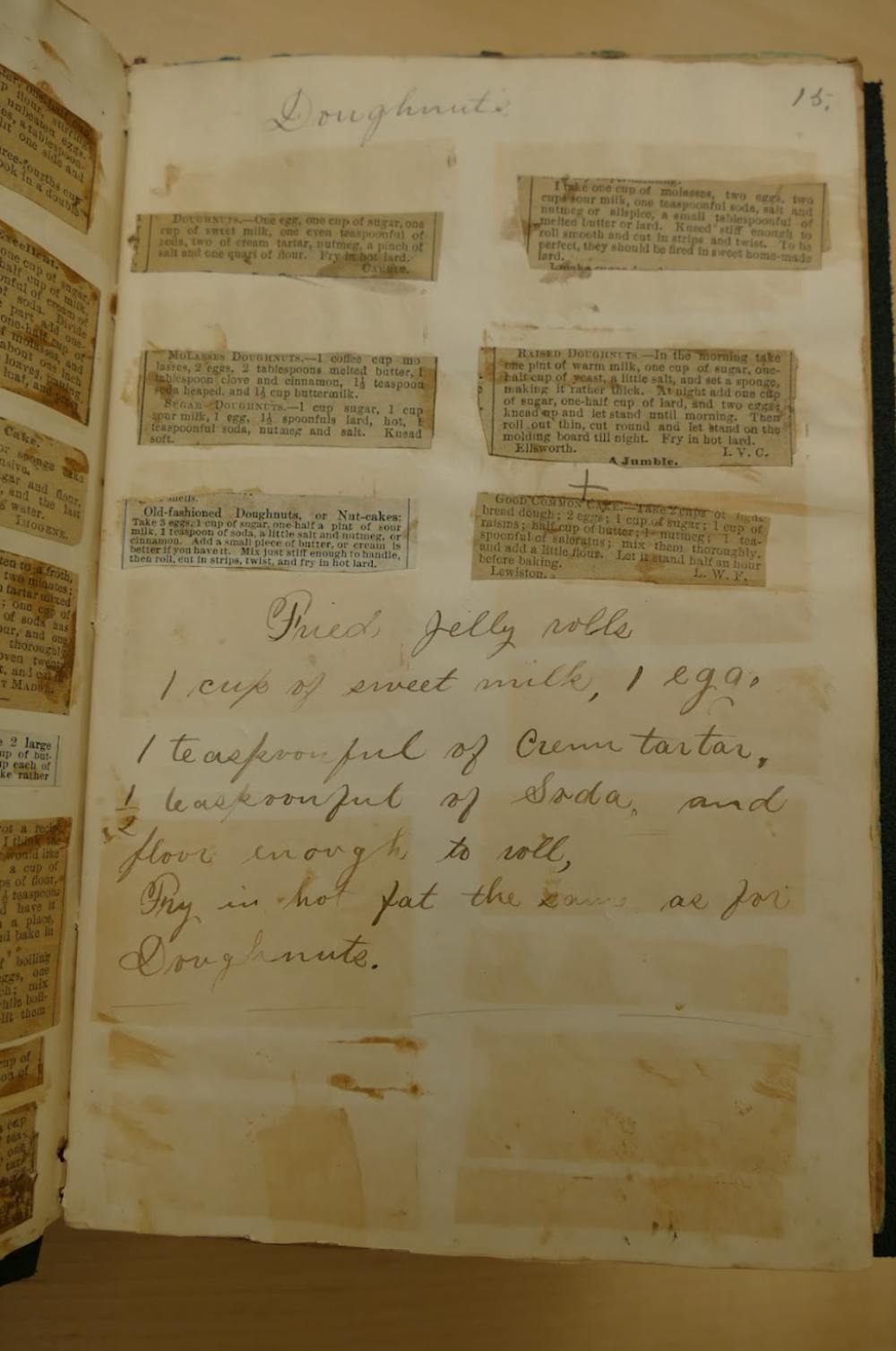

In the bracing winter cold, the prospect of warm, freshly baked treats seems all the more tempting. This homemade recipe book from the late 19th century offers a view into baked goods that people would have enjoyed 150 years ago, containing handwritten recipes and recipes cut and pasted from newspapers. Within the blue cover paper, recipes for all kinds of cakes, cookies, doughnuts, pies and breads abound.

The recipe book was bought in 2014 by Emily Bogin ’16 as part of an exhibit Bogin curated called “Good Things to Eat: Recipes and Communities from 1827 to the Present.” A Special Collections blog post wrote that, “[t]his new exhibit focuses on the ways in which food has, and continues to facilitate community, both at Middlebury and beyond.” The recipe book alludes to a rich historical context, from the shifting social landscape to important technological and economic developments of the time.

The book hints at how American gender roles were changing in the latter half of the 19th century. At the time, it was popular for women to begin using dinner parties and social events to advance the social status of their families and husbands. While this phenomenon tied women’s reputations and identities to domesticity, it also gave women some responsibility over the family’s social mobility and provided a novel way for them to contribute economically. As these dinner parties became more popular, women needed to learn how to prepare food appropriate for such events. Recipes and cookbooks targeted towards these special occasions thus gained importance.

The ingredients in the recipes correspond with items found in modern pantries. Baking soda, appearing in many recipes in this book, became industrially manufacturable in the latter half of the 19th century due to the invention of the Solvay process. Wheat flour also grew in popularity during this time period. This rise in American wheat consumption stemmed from improvements in flour milling techniques, trade infrastructure and agricultural development. Sugar also became a more prominent baking ingredient. Whereas previously, alternatives such as molasses or brown sugar may have been cheaper, new processing methods now made white sugar less expensive and more accessible. ‘Domestic advisor’ authors at the time began to advocate white sugar’s merits in baking. Due to all of these innovations in ingredients, cake recipes became more elaborate and varied in the latter half of the 19th century.

I decided to try baking one of the handwritten recipes from the recipe book, and settled on something called “Graham Gems,” muffin-like cakes that were extremely popular in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, according to the Ebenezer Maxwell Mansion museum. They are named after Sylvester Graham, an early American advocate of dietary reform. I decided to make these because I had never heard of this baked good before and wanted to revive this bit of historical popular culture.

The recipe calls for Graham flour, regular flour, “sour milk,” baking soda, molasses and salt. Unable to find Graham flour, which is more coarsely ground, I substituted standard whole wheat flour. I also used buttermilk instead of sour milk; both provide the acidity needed to activate the baking soda. Like most of the recipes in the book, there were almost no assembly instructions, only a note to “bake in a quick oven.” After mixing everything together, I baked at 380˚F, which I thought might approximate a “quick oven” (I now believe the recipe may have required a hotter temperature for the ‘gems’ to rise more effectively). The final product was very slightly sweet, plain-looking, chewy and somewhat dense — more like bread than a modern muffin or cake. I don’t think this health-conscious recipe is very representative of the more indulgent desserts in the rest of the book, many of which include cupfuls of sugar, butter or lard, but it does carry some interesting history.

In historical recipes, where instructions may be sparse and the quality or meaning of ingredients may have changed, it can be hard to know whether modern attempts at re-creation are accurate to what the original version would have been. Regardless, this recipe book provides a glance into one kitchen of the past, offering a representation of greater themes and trends of the time.