Dozens of students, staff, faculty and community members gathered in a circle in the Dance Theatre of the Mahaney Arts Center on Wednesday, March 9, stretching and waiting as light, upbeat music filled the room. Visiting Assistant Professor of Dance Lida Winfield entered and introduced the event, the first of a multi-part series entitled “Movement Matters: Global Body in Conflict.” Winfield explained these new events as part of a recent grant given to the Dance Department on behalf of the funding from the Kathryn Wasserman Davis Collaborative in Conflict Transformation.

“Dance has always been about conflict and always about transformation, but rarely have both been put together,” Winfield said.

The grant has allowed the department to hire several artists in residence, who offer master classes and lunch talks, and meet with students and staff to learn about creative problem-solving. Although it might seem unconventional, dance provides an ideal avenue to explore conflict-related goals such as talking across differences and creating competency and awareness. This series of events is intended to produce a comfortable yet challenging space to invite in complexity and personal experience.

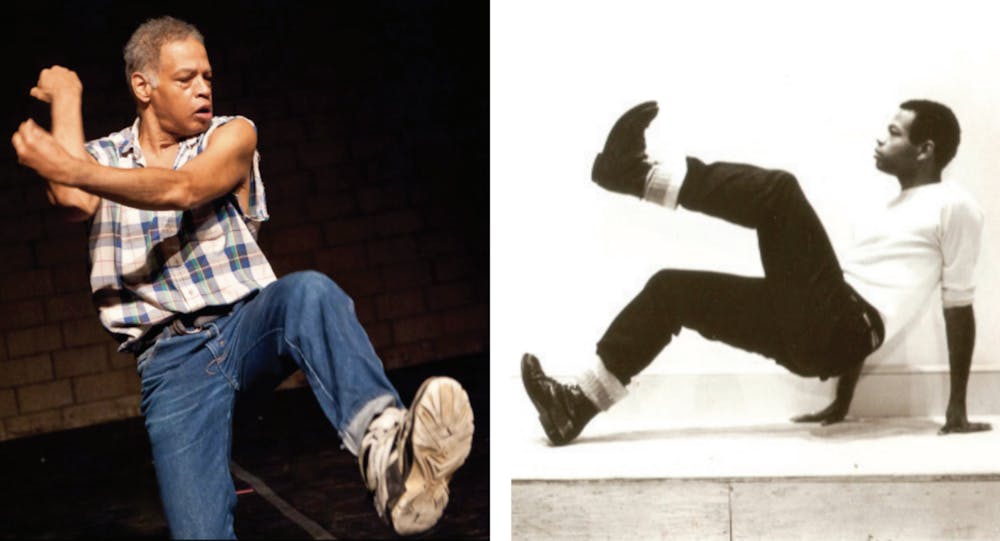

Picture sitting on the floor with 50 strangers who are all kindly looking at you and saying your name in unison right after you introduce yourself. After having done too many introductions to count during my time at Middlebury, I have grown skeptical of how welcoming they can actually be, especially in a large group. For this reason, I was pleasantly surprised that such a small change as having the whole group parrot back your name in unison could turn what often feels like a cold formality into a warm, welcoming embrace. If there’s anyone who could have led such an inclusive and welcoming type of introduction for a dance event about conflict and movement, it is Ishmael Houston-Jones.

The dancing began shortly after Houston-Jones, the first guest artist to come to Middlebury under this new structure and funding, entered the dance space. Houston-Jones, best known for his choreography, teaching and improvisational dance, got the movement started quickly by having us walk around. Students began milling around a relatively small dance floor and navigating the space, while being mindful not to bump into anyone else. It was difficult, and, to make matters worse, the next instruction was to start randomly changing direction every couple of steps. For me, a 6’2”, relatively uncoordinated and inexperienced dancer, walking in this way led to bumping into others and required a lot of self-awareness. The next step was to intentionally brush up and bump into others. I was quite skeptical of this being a comfortable experience, but I slowly started to understand the non-verbal, subtle ways of communicating by using eye contact and reacting to, and listening to, people’s body language. Through the fleeting glances into the eyes of others and gentle brushing of shoulders, I even felt like I was starting to “get to know” some of the other dancers, without having ever met them before the workshop.

The next step of the workshop was even harder. After a slight brush or contact, we were encouraged to stay connected physically to whomever we ran into for a few seconds. Initially, I was quite nervous for this step, because it meant sharing the direction and pressure of touch with a stranger and negotiating that commitment in real-time. This led to several off-balance and awkward stumbling moments. Yet, in other moments, I was able to explore some ways of moving that felt really freeing. By this time, I had put some of my self-consciousness to the side and suspended my disbelief as we moved into the main contact improvisation exercises.

Sasha Wintersteller ’26.5, Mark McGoey ’26.5 and Simon Leiderman ’26.5 attended the workshop, inspired by the same kinds of improvisational techniques that they are learning about in their first-year seminar, Collaborating Across the Arts. From this class, all three of them seemed used to discussing the emotions that come up in a setting like this. Wintersteller and McGoey were partners in an activity where one partner, with eyes closed, is led by the other, and they both reflected on some of the challenging and easy parts of an exercise like this that requires immense trust and courage. “I was kind of stressed about not bumping into walls and other groups, but I also really appreciated the chance to take a risk,” McGoey said.

McGoey’s sentiment matches with one of Houston-Jones's most repeated goals of the whole activity, which was to "embrace the awkward." Unlike me, others did not necessarily feel the awkwardness, but they appreciated the challenging aspects of moving with people in novel ways. "For me, I felt comfortable, but [I] would be excited to bring this feeling of vulnerability into my everyday life,” Wintersteller reflected.

"I feel less comfortable outside of a dance class, but also wish I could take some of that risk more often," Leiderman echoed.

My partner for the same activity was Lisandra Tusen ’26, who had been on a competitive salsa team for five years. Through that type of dance, Tusen was used to working with inexperienced dancers, and she reflected on what it meant to share leadership across skill levels. I wanted to hear whether she saw a link between this shared experience and some of the challenges of a world with conflict.

“Dance is a beautiful way to find connections between people you don’t know, which is really important because we live in a scary world, and I really felt that energy,” she said.

The next Movement Matters: Global Body in Conflict visiting artist is Jumatatu Poe, who will be visiting and leading a lecture Tuesday, March 28 and a workshop Wednesday, March 29. Find out more at go/dance.