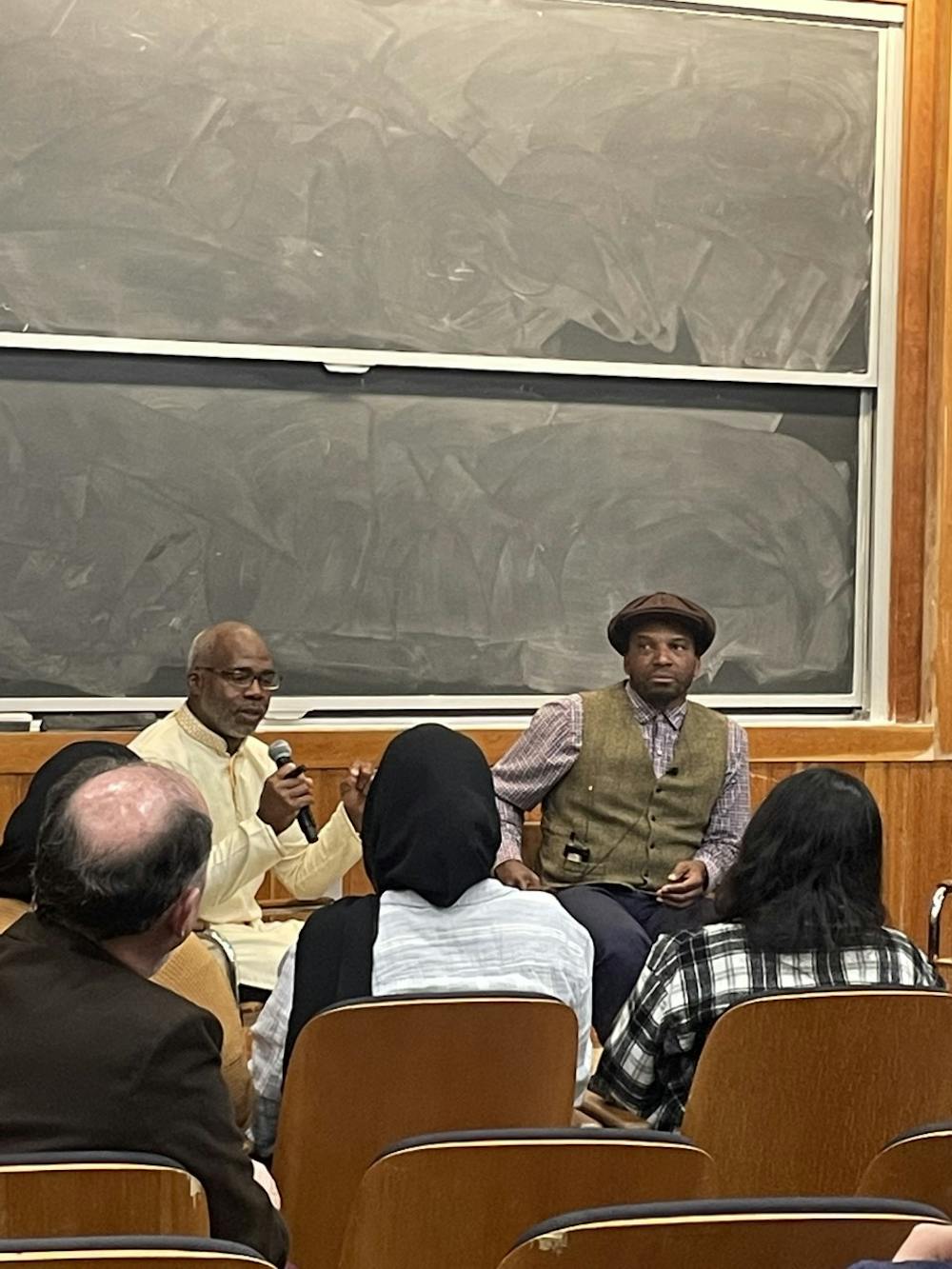

Students and faculty gathered in Bicentennial Hall to listen to authors Ibrahim Abdul-Matin and Rhamis Kent discuss an Islamic solution for climate change on May 3. The event was co-sponsored by Faithfully Sustainable, Muslim Student Association (MSA), the Climate Action Capacity Project and Environmental Affairs committee, the Charles P. Scott Center for Spiritual and Religious Life and the New Perennials Project.

Faithfully Sustainable is a national organization dedicated to bridging the gap between faith and environmental stewardship by allowing young Muslims to participate in conversations about pressing issues. Since the organization’s creation in 2020, the climate crisis has been one of its major focuses, so it was very excited to welcome Abdul-Matin and Kent — two prominent leaders in the climate movement — to the first in-person Faithfully Sustainable event at Middlebury since Covid-19 began.

“I knew that I wanted to be involved somehow to be an active participant in climate change,” said Kadjahtou Balde, a co-founder of Faithfully Sustainable. “Especially given that I learned a lot about how my faith approached stewardship; what it says about our responsibility as human beings to the planet and to each other. I wanted to explore that curiosity and find how I could be an active participant in this work.”

Abdul-Matin is the author of Green Deen: What Islam Teaches About Protecting the Planet, a book that examines environmental issues through an Islamic lens and emphasizes the principles that are important in the fight against climate injustice. Abdul-Matin said he hoped that by writing this book, he would facilitate conversations between young people and elders that impact the climate change movement. He wanted anyone from his eight-year old nephew to his 70-year-old aunt to resonate with his words, regardless of whether or not they were Muslim.

“There’s no other planets that we can live on, this is what we’ve got, so no matter what you believe in, we’re here together,” Abdul-Matin said.

Abdul-Matin emphasized the need to foster a community of people across multiple generations and different religious identities that are all dedicated to collaboratively fighting the climate crisis.

“We need to be in relationship with each other if we’re supposed to be in the right relationships with nature, with God and all these other elements,” Abdul-Matin said. “We need to be better at communication.”

Both speakers also discussed how deeply religious people have made important scientific discoveries because of the unique aspects of their faith.

They described how religion can be a useful tool to both understand the science behind how the climate crisis occurred and strategize ways to combat it.

“If you look at the history of Muslims, as a community they have arguably done the most to open the doors to scientific discovery, and certainly the discoveries that led Europe to coming out of the Dark Age,” Kent said. “All the great Muslim scientists, mathematicians, researchers, what have you, are all deeply religious people.”

Kent emphasized that the combination of both metaphysical and ethical frameworks produces the most success. Kent described the “ethical fractal” that begins with ethics–the management of the individual–then branches to ecology–the study of the household–and then to economics–the management of the household and then finally to politics–the management of the society.

“If you can’t manage yourself, or if you’re in a community or group of people that are unable to manage themselves, then therein lies the problem,” Kent said.

The ethical fractal can be used as a tool to combat the climate crisis. It all starts with the individual who wants to make change, and then it slowly expands into pressuring the government to make policies that will manage society and manage the climate crisis.

Abdul-Matin and Kent have not only found a way to examine the climate crisis from an Islamic lens, but also to implement key values of their religion within the movement. They shared that through consistency, collaboration and conversation, real change can be made to combat climate change.

Abdul-Matin recalled waking up in the middle of the night and watching his father pray. This memory highlighted to him the importance of consistency via setting examples. In terms of the climate change movement, Abdul-Matin stressed that if one person can be consistent with their actions, like his father was with his faith, it will help to motivate others to do the same.

“It’s a very real thing that you actually have to put practice and rhythm into. The way we learn is not just by saying things, and the way young people learn is not just by hearing things, they learn by what they see people do,” Abdul-Matin said. “The way we treat the planet is a reflection of the way we treat ourselves. How we are and how we treat everything around us is how we see ourselves.”

Abdul-Matin and Kent provided wisdom about how to best commit to the climate change movement both within the Middlebury community and beyond — jump into conversations with fellow students and those much older, get involved in any way possible and welcome all the different perspectives throughout the world.

Ellie Trinkle '26 (she/her) is the Senior Arts and Culture Editor.

She previously served as a News Editor and Staff Writer. She is a Film & Creative writing double major from Brooklyn who loves all things art. You can typically find her obsessively making Spotify playlists, wearing heaps of jewelry, or running frantically around campus.