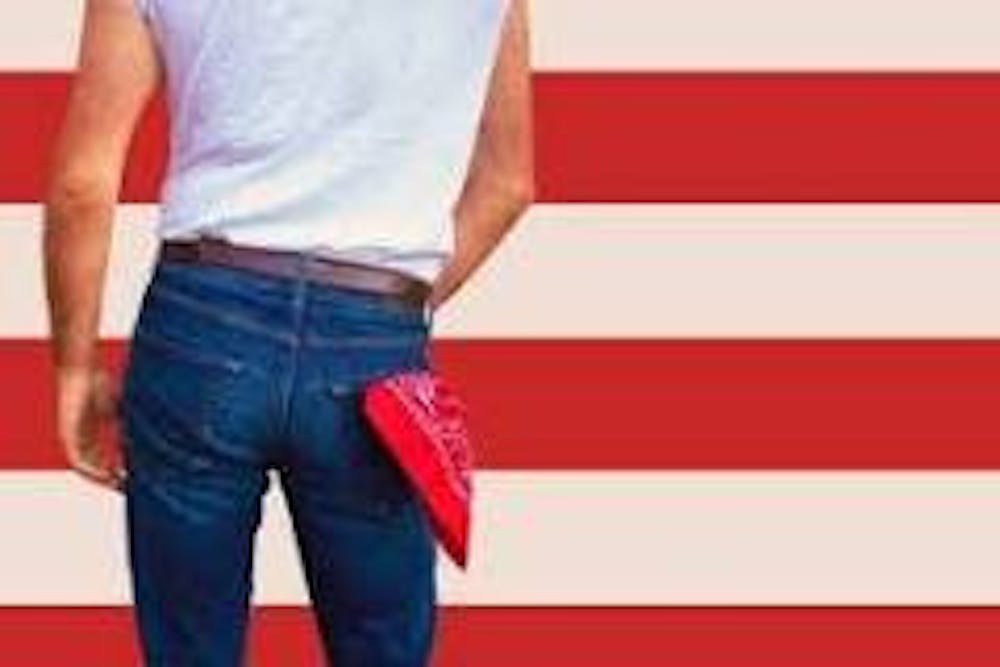

In an evening of fatherhood, brotherhood, toxic masculinity and death, “Dad Rock,” Beck Barsanti ’24.5’s acting thesis explored what it means to be a man in the modern world. The work opened on Nov. 2 and was directed by Gavin Richards ’25.5, Bri Beach ’23.5 and Maggie Blake ’24.

Situated between “Greek Tragedy,” a play about the impacts of being an influencer, and “The 25th Annual Putnam Spelling Bee,” a show about middle school angst and social pressures at a spelling Bee, “Dad Rock” added a nuanced maturity to the Middlebury theatre scene this semester. It is a grounding story for the season, exploring the complexities of manhood across time periods and settings.

Barsanti’s play strings together scenes from playwrights Tolkien, Mitchel, Shepard, Melville, Stoppard and more to explore manliness. At times, Barsanti takes on the roles of brother, God, captain, father and actor.

“‘Being a man,’ to me, has nothing to do with bottling emotions, protecting anything, or toughing things out. Being a man today means doing whatever brings you closer to why you are comfortable with a masculine identity, whether that's a male identity or not,” Barsanti wrote in an email to The Campus.

The show opens with a short scene featuring two hobbits before giving way to a 1970s home in southern California where Sam Shepard’s brothers Lee (Barsanti) and Austin (Owen McCarthy ’25) sit at a table discussing plans for an upcoming trip. Though Lee is an alcoholic and a thief, while Austin is a successful playwright, Lee claims to be a better storyteller because he has lived in the West. In a later scene, the brothers’ mother (Charlotte Roberts ’25.5) returns to her own house only to find it trashed by her sons, who are fighting about their own ambitions. Austin ends up slaying his brother so that he can escape, viscerally demonstrating the violent combination of ego and toxic masculinity.

Next, the performance jumps back a few hundred years to the medieval world of Jared Michael Delaney’s “Falstaff and the Endless Machine.” Jack, a young, honorable man, seeks justice for Doll’s (Annabelle Iredale ’23.5) abuser. Self-conscious of the stigma attached to her work as a prostitute, Doll reminds Jack that despite his noble efforts, men of status and class will always escape justice because the sheriff does not care about the law, only about money.

Eventually, Jack’s character bleeds into Hades, beginning with a song from Anais Mitchell ’04’s “Hadestown.” Hades, with his deep, booming bass voice and leather attire, embodies masculine strength and control. He commands his workers to build him a wall to protect his kingdom, urging them to keep out the enemy, political opposition and views that challenge his own. Hades builds an echo chamber, a cordoned-off world view. In a later scene, Hades sings about his fear of Orpheus cracking his world order, threatening his domain, his position in society and his masculinity.

In addition to the dystopian masculine insecurities of Hades, Barsanti illustrates the dysfunctional and chaotic sexual desires that interfere with his fatherhood through performing an excerpt from “Coffin.” In this scene, an alcoholic dad tries and fails to understand and connect with his teenage son. It highlights key factors of adolescent independence like driving, drinking and having one’s first sexual relationship, while also illustrating the fragility of life. In the end, the father commits suicide, leaving his son with an empty home with nowhere to go.

Ultimately, “Dad Rock” ends with the futility of death. The penultimate scene of the show is from Tom Stoppard’s “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead.” The two young lads resignedly accept that they would die at the behest of Lord Hamlet. They attempt to kill an actor who is on board their ship to London but are outwitted. The actor’s durability helps them discover the futility of their prognosis because they are only dead on paper.

Students and community members who attended the performance reflected on the play’s intense emotionality allegories of masculinity.

“I would absolutely recommend it. I just love the actors and their intensity, the rigorousness of the show… there were definitely some true emotions coming out,” Gabe Rocama Katowitz ’26.5 said.

Melissa Powderson, a family friend of Barsanti who worked with him during his high school theatre performances, also mentioned the strong emotions she observed during the show.

“I thought it was really amazing and it was very intense. To change from the different emotions between the scenes was so incredible that one could be present from one scene to the next. It was magnificent and all the actors were incredible,” Powderson said.

By somewhat chaotically combining nine divergent scenes about masculinity and fatherhood by seven different playwrights, Barsanti illustrates the fragility and futility of toxic masculinity. He helps his audience escape the institutions which “help us to forget the pain rather than confront it; asking us to feel anything but the feeling itself.” directors Gavin Richards, Bri Beach and Maggie Blake wrote in the director’s note.