In the summer after my first semester at Middlebury, I read “The Idiot” by Elif Batuman, the novel to which “Either/Or” is the sequel. Both books center Selin, a Turkish American woman at Harvard beginning in the year 1995.

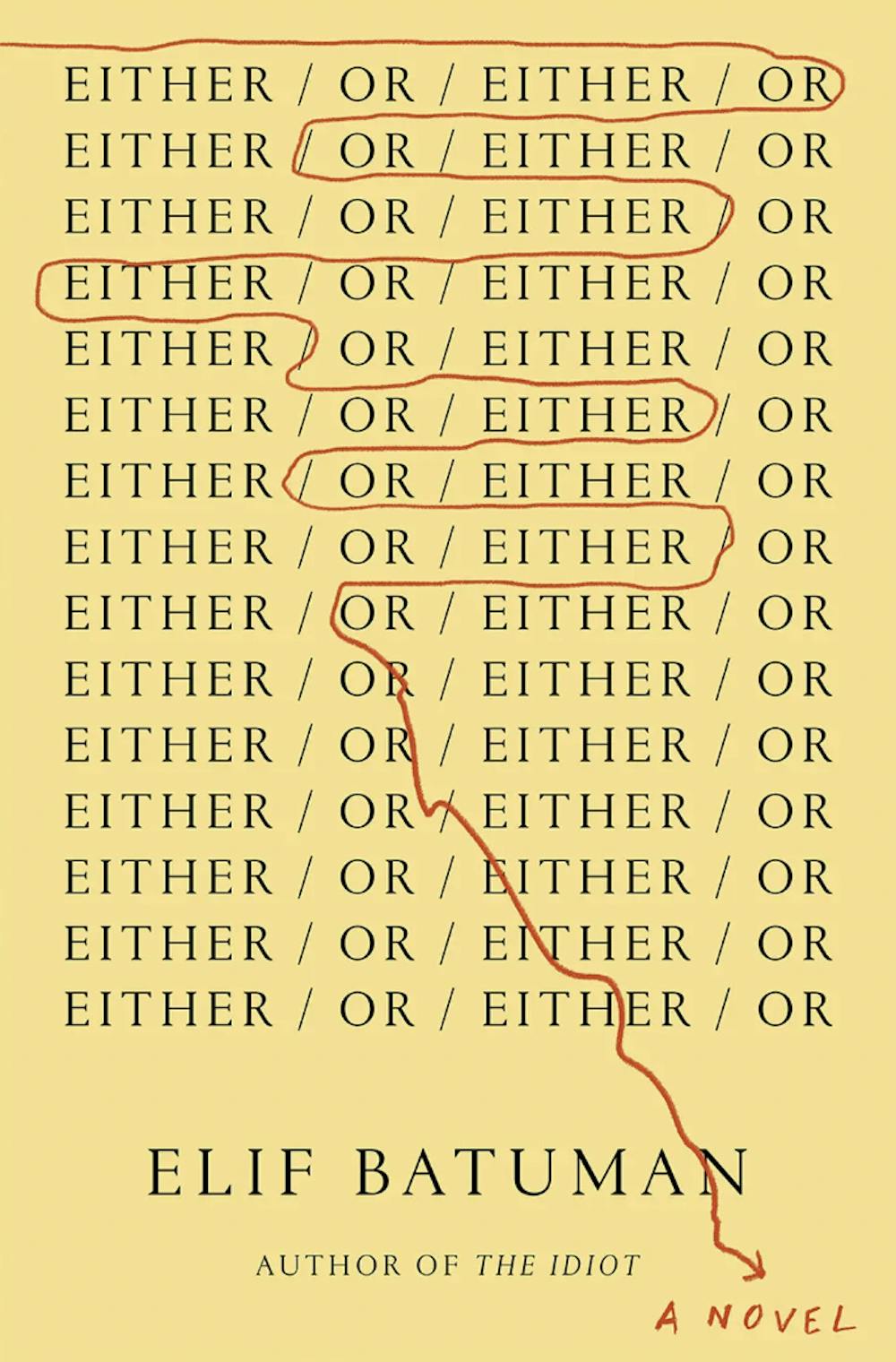

Named after the well-known work “Either/Or: A Fragment of Life” by Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, Batuman’s “Either/Or” details Selin’s sophomore year of college. It chronicles her retrospections about her freshman year and her approach to a world full of ostensibly mystifying contradictions. She turns to literature — her newly declared major — for solace and answers.

“The Idiot” is named after Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novel by the same title and follows Selin’s freshman year. She is sharply observant, comically blunt and fascinated by her new college life, noting the quirky behavior of her roommates, throwing herself into her Russian and linguistics classes and putting the fresh (and powerful) invention of email to use.

Selin forms a friendship with the energetic and passionate Svetlana and an interest in the Hungarian senior math student Ivan, who gets her a summer job teaching English in a Hungarian village. Selin wants to be a writer and sets out after “interesting experiences” — experiences she considers worthy of fiction.

The first-person narration in “The Idiot” seamlessly blends together what Selin learns in her humanities classes and in her personal life. Splashes of social spontaneity provided by her residential college and her incessant train of curious thought while moving around campus charmingly reminded me of Middlebury and inspired me to consider my own college life in her dissecting, patchwork way.

While “The Idiot” felt a little flat or under-explained at times, I was intrigued enough to pick up Batuman’s 2022 sequel. “Either/Or” is my favorite novel, and one I think many Middlebury students would enjoy reading.

It stands out from “The Idiot” in how much closer the reader comes to Selin. We intimately see her deeply analytical, often cynical thoughts, propelled by her acute observation and endless mental bank of memories and stories. She searches obsessively for the answer to the overarching question: How should I live?

Early in the story, Selin adopts a fascination with Kierkegaard’s book, which is separated into two parts: one on the “aesthetic life” and another on the “ethical life.” According to Kierkegaard, the “aesthetic life” occurs when one lives for themselves and seeks beautiful but perhaps fleeting experiences, while the ethical life exists when one adheres to moral principles and traditions, likely including getting married and having children. Arthur C. Brooks recently wrote about Kierkegaard’s ideas for The Atlantic, describing these different lives as methods that can be employed throughout the changing phases of one’s actual life.

While Selin is drawn towards an aesthetic life, Svetlana decisively follows an ethical one, a core difference that the friends often discuss in the dining hall and on the floor of each others’ dorm rooms.

“I was still the kind of person who thought it was interesting to see what happened if you only ate cashews for a week,” Selin writes as she watches Svetlana begin a new diet.

Selin’s unconventionally belated first encounters with parties, alcohol and hookup culture, as well as incompetent mental health services, weekend trips with friends and visits back home, are saturated with references to the books and music she consumes as she searches for the answers to her questions about life. She approaches situations purely empirically and then deconstructively, as if they are happening for the first time and require immediate dissection. Selin comes off sometimes as wonderfully perceptive, and other times painfully oblivious.

Batuman weaves ample humor into Selin’s narrative. She manages to make both mundane and unusual scenes — an overcrowded Pilates class or finding a stingray in her suite’s sink, for instance — funny, mostly by way of her protagonist’s witty reactions to them.

“I barely had time to gulp down half a bowl of Cracklin’ Oat Bran — the most filling cereal, in almost a sinister way — before [Svetlana] made us leave for Russian,” Selin narrates. “We were the first people there. At first it seemed like I might have time to tell her about Kierkegaard, but I had barely gotten started when our classmate Gavriil came in. Gavriil had a wiry build and fluffy hair resembling that of Mozart in the movie Amadeus, and was always climbing things. You might look at a library or a church and see something on the wall, and it would be that guy, Gavriil.”

The songs “Criminal” by Fiona Apple and “Killing Me Softly With His Song” by the Fugees, the novels “Nadja” by André Breton, “Anna Karenina” by Leo Tolstoy, “The Portrait of a Lady” by Henry James and even the self-help book “The Rules: Time-Tested Secrets for Capturing the Heart of Mr. Right” by Ellein Fein are all pieces in the imperfect puzzle of the human condition she spends the novel toiling to fit together.

Readers do not need knowledge of the references in “Either/Or” to appreciate them, though familiarity here and there certainly enhances the experience. They are not unexplained allusions, but rather material that we feel we are discovering alongside Selin — we get the sense that she is more perplexed about their true meaning and application to the human condition than we are.

There are many passages in which Selin reflects on her search for a balance between all the material, memories and conversations she absorbs and weighs against each other, fueling a ceaseless game of ping-pong with herself — sometimes light-heartedly, sometimes in distress.

One quotation from the middle of “Either/Or” well captures its spirit and its relevance to our lives as Middlebury students: “How brief and magical it was that we all lived so close to each other and went in and out of each other’s rooms, and our most important job was to solve mysteries. The temporariness made it all the more important to do the right thing — to follow the right leads.”

That’s enough of my rhapsodizing — go discover Batman’s novels, particularly “Either/Or,” for yourself. Young adults figuring out the world (temporarily) surrounded by such a tight-knit social space and the liberal arts just might find something that resonates.

Madeleine Kaptein '25.5 (she/her) is the Editor in Chief.

Madeleine previously served as a managing editor, local editor, staff writer and copy editor. She is a Comparative Literature major with a focus on German and English literatures and was a culture journalism intern at Seven Days for the summer of 2025.