Content warning: this op-ed contains mention of self-harm and suicide.

They say that to have an eating disorder is to be at war with yourself. Likewise, to paraphrase Baudelaire, they say that the greatest trick of the enemy is to convince you that there is no war. Overcoming an eating disorder is challenging because it requires you to choose to be at peace with your body all the while surrounded by others still waging war against their own.

Treatment is what turned the tide in the war against my body. This week, Feb. 26 to March 3, is Eating Disorders Awareness Week, and I am deeply concerned that Optum (also known as United Health Group) has chosen to mark the occasion by closing treatment centers, including one that helped save my life, Cielo House. I am sharing my story with the Middlebury Community to rally support for my petition to keep 25 eating disorder treatment programs open and save lives like mine.

I was young when I began waging war against my body. Bullying was my call to arms. Innocent as I was, I did not know that it was bad to be fat, let alone that being fat would lead me to experience social exclusion. Yet, ironically, waging war against my body led me to experience even greater social isolation.

As our ancestors beat plowshares into swords to prepare for battle, as a child, I turned my toys into tools for making war against my body. The tape measure purchased for sewing camp and the Wii Fit purchased for Christmas became tools for body checking. The inline skates purchased for my birthday became a tool for compulsive exercise. A science camp nutrition lesson became a tool for water loading and caloric restriction. Waging war against my body grew lonely at times. Yet in those moments when the pain of my loneliness led me to question my behaviors, it was as if my eating disorder hushed me, saying, “Shh, shh, just lose the weight and then you’ll be happy.”

Moral relativism also helped me to justify the means through which I waged war against my body as I subjectively compared my behaviors to those of my friends. For instance, as I listened to one of my best friends tell of how he used self-h*rm to wage war against his body, my tools of war seemed like mere child’s play.

Somehow the enemy convinced the grown-ups who might have called for a ceasefire to dismiss the warning signs. Doctors dismissed the warning signs of anemia and bradycardia (a slower than normal heart rate). Therapists dismissed the warning signs of elaborate food rituals and extensive food rules. Coaches dismissed the warning signs of dizziness and near fainting spells. Rather than calling for a ceasefire, some of the grown-ups urged the war effort, saying things along the lines of, “You lost weight. It looks good.” So, the war waged on.

In my years at Middlebury, it seemed all too easy to find supporters of the war effort. As an underclassman, it was peers responding to dining hall discussions of my food rules and dietary restrictions with admiration, remarking along the lines of, “How do you do it?” In my sophomore summer field research, it was participants making comments about my body along the lines of, “You’re so tiny” and “I was just about your size.” My junior fall, it was guys I had just met who told me, “I’m only hanging out with you because you’re cute” or “I thought I was going to get a date.” My junior winter, backstage before a performance asking for help tightening my costume, it was a fellow performer saying, “I wish I had it like you.” These and other interactions were constant reminders of my fears that my belonging was contingent on me fitting into a standard of beauty that was hipless and thin. Those fraught memories stoked the fear that helped keep the war effort alive.

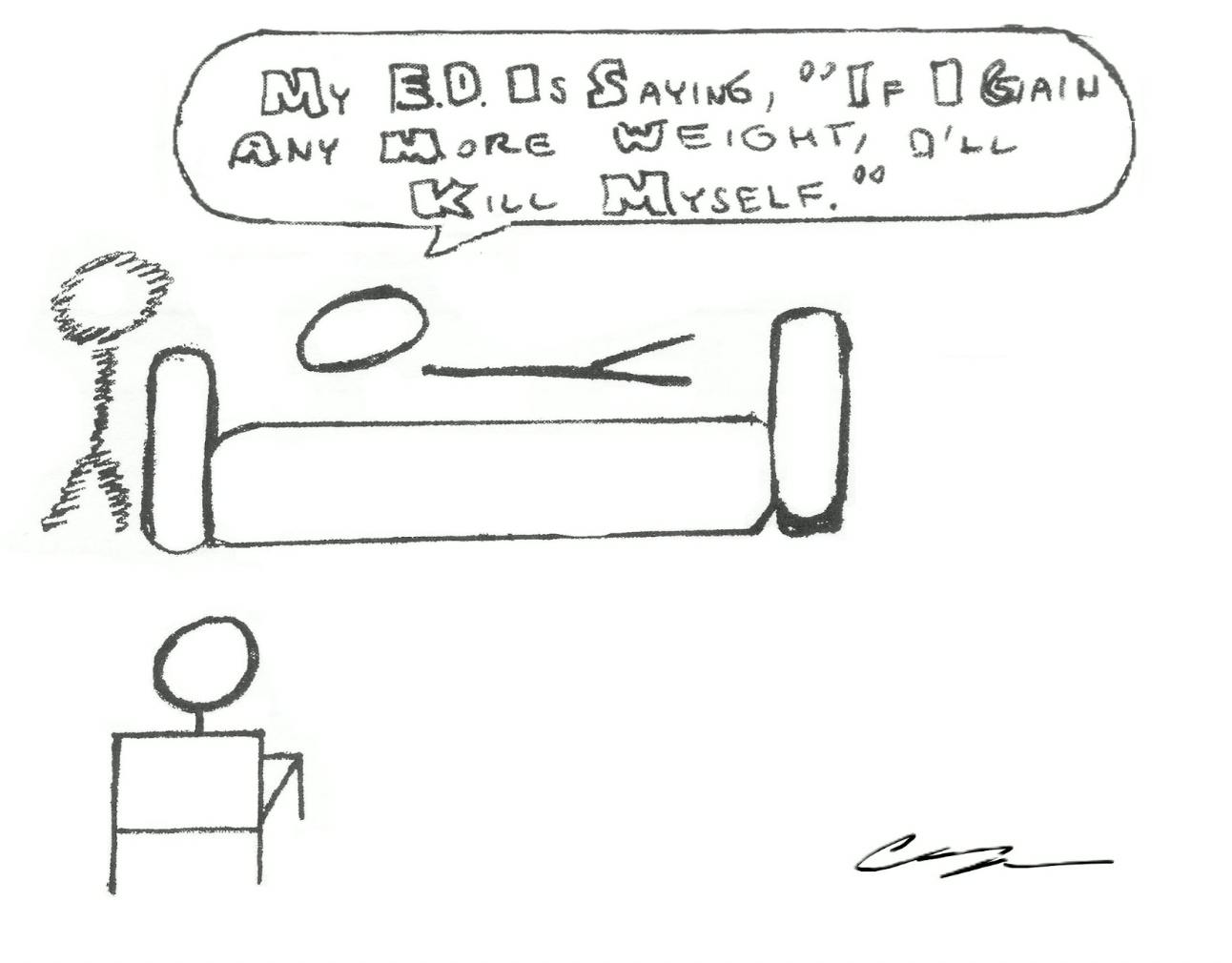

It took intensive treatment to help me recognize that I was at war with my body. Through individual and group therapy, I finally came to terms and said the quiet thing that my eating disorder was whispering to me out loud: “If I gain any more weight, I am going to k*ll myself.” It was only then that I understood that my life was at stake.

As I read more about eating disorders, I learned that my war against my body was greater than me. Books such as “Fearing the Black Body” taught me how white supremacy and other forms of hegemony benefit from women of color, like me, waging war against our bodies. Me and others being at peace with our bodies is disruptive to systems of capitalist exploitation, in particular a $70 billion diet industry, which thrive off of us being perpetually discontent with our bodies.

Yet, this head knowledge alone was insufficient to save me from my war against my body. Rather, drawing from twelve-step methods, I realized that for me to come to a place of peace with my body, I had to admit that I was powerless to my eating disorder, and I needed my higher power, my God, to save me from myself and for my community to hold me accountable to my recovery.

If my story has moved you, please consider supporting me and others seeking to be at peace with our bodies by signing my petition to tell Optum to stop closing eating disorder treatment centers.