Writer and performer Rachel Mars brought her one-woman play, “Your Sexts Are Sh*t: Older Better Letters,” to Wright Memorial Theatre as a part of Middlebury’s 2023-24 Performing Arts Series.

Through readings of various artists’ love letters and projections of anonymous explicit digital messages, the Feb. 29 and March 1 performances served as intimate — at times overwhelmingly so — explorations of desire, the forms used to express it and the politics that dictate it.

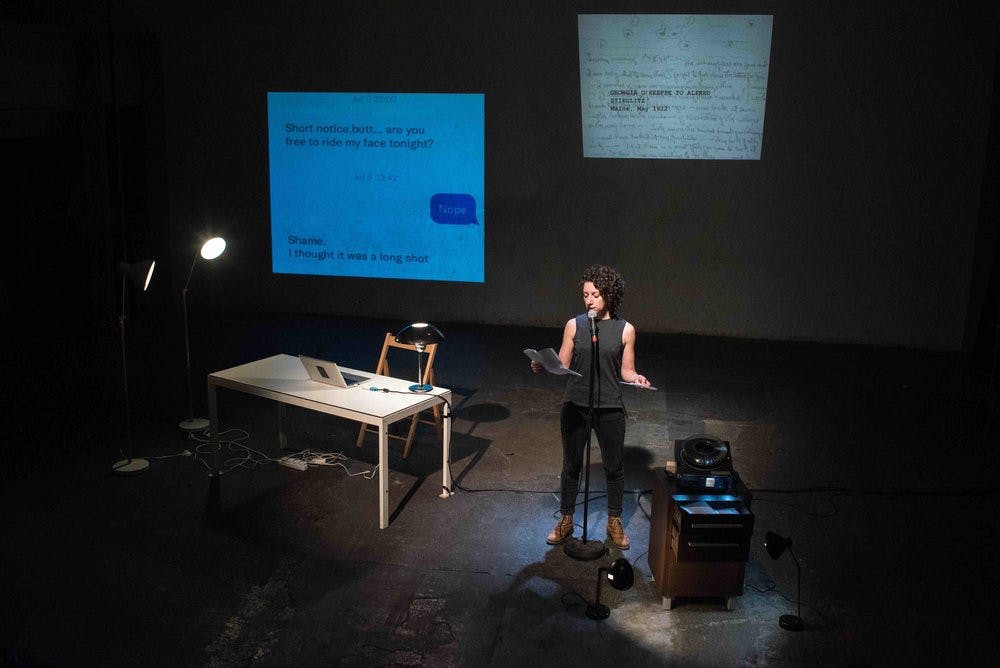

At the top of the play, Mars entered the stage quietly, passing purposefully through a triangulated scene: in one corner was a short dresser and carousel slide projector pointing at a screen, while in another a writing desk with an open laptop on it and the show’s title card cast on the black backdrop.

Stopping first at the dresser, Mars opened a drawer, pulled out a stack of envelopes, untied them and replaced all but one. She removed the letter inside, unfolded it and began to read aloud into a microphone a letter written by Irish author James Joyce to his wife, Nora Barnacle. Quickly, she sent the audience into raucous laughter with details of Joyce’s acute appreciation of his wife’s mid-intercourse flatulence.

Mars alternated between reading letters and clicking silently between the slides of suggestive texts — brief and unembellished in comparison to the letters, but no less dirty.

The third element of the show, performed from a slightly raised platform where Mars leaned conversationally against a desk, microphone in hand, was an original, autobiographical letter that described Mars’ lifelong journey as a queer woman. In the Q&A following the show, Mars framed the letter as a way of “coming into [her] sexuality through writing.”

The show’s inception was indeed inspired by this first letter. “In June 2016, immediately after the Brexit vote I was depressed and in upstate New York,” Mars wrote in the playbill. Trying to cheer her up and provide some comedic relief, a friend Mars read her Joyce’s letter off of his phone — and it worked.

Using the Joyce letter as inspiration, Mars began conversations with sexologists Jana Funke, an associate professor of English and Sexuality Studies at the University of Exeter, and Lena Wanggren, a research fellow of English and Scottish Literature at the University of Edinburgh, about a play based on the premise of love letters.

Research for the piece began with the unveiling of love letters from creatives like Georgia O’Keefe and Radclyffe Hall, former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and a monk named Brother Augustine, all of which ultimately appeared in the show alongside a collection of text messages from friends, colleagues and strangers.

The readings were accompanied by the voices of Olivia Newton John (“Physical”), Diana Ross (“I’m Coming Out”) and Janelle Monáe (“Make Me Feel”). This musical element was sometimes more distracting than conducive, however, and at points, the music was so loud that it was difficult to focus on Mars’s voice at all.

Minimal but poignant set dressing made for an intimate audience experience, particularly the inclusion of floor and desk lamps to subtly illuminate the corners of the stage.

After the performance, Professor of Theater Claudio Medeiros mediated a Q&A between Mars and the audience. Mars described her creative process, saying that while some elements of the production evolved — for instance, the show was originally a three-person production — others have always been central to her thesis.

Letters from Joyce to Barnacle were consistently used throughout the play, typically followed by a transition to a slide stating, “Nora Barnacle to James Joyce, 1909,” and then Mars, standing, sighing, at the microphone. She eventually explained, “We don’t know what happened to Nora’s letters, we couldn’t find any of them. Probably the patriarchy.”

At the very end of the play, the carousel returned to the slide, “Nora Barnacle to James Joyce, 1909,” but this time, the spotlight on Mars dimmed and the raspy, authoritative female voice of actress Lesley Ewen came over the speakers to read an imagined response from Barnacle to her husband. The letter was enthusiastic, sensual and, at some points, plain nasty.

When asked about this segment of the show, Mars explained that her intentions were mostly political — she wanted to give an empowered, explicitly consensual and indelicate voice to Barnacle, who had been, until now, silenced in the archives of her own love story.

Nora’s response was incredibly honest and artful, but also long and unrelenting. Mars later described this as an especially divisive aspect of the show for past audiences.

Towards the latter half of the show, the false dichotomy of the title became clear — newer, more immediate forms of expressing desire aren’t necessarily worse or more crude than they used to be. As Mars put it, “It’s just a matter of knowing your form.” To this end, a main thesis of the performance seemed to be that intimacy isn’t created by flowery language or (literally) fruity metaphors. Instead, it is sparked by knowing your partner — from their body to their handwriting to their domestic quirks — and by putting that familiarity into words.

Mars’ performance became more overtly female and queer in focus over time, serving as a captivating demonstration of the restraint central to that experience, and the pleasure found when that restraint is lost. Doubly, “Your Sexts Are Sh*t: Older Better Letters,” views the act of writing one’s desire as a reflection of the self and, for some, a physical preservation of marginalized identity.