This past summer, our basement flooded. We had rented a house with five friends here in Middlebury, and were looking forward to Vermont’s sunny days, swimming holes, cookouts and hikes in the woods. Instead, we were met with wildfire smoke, monthslong rainfall and flooding. Carrying wet, moldy furniture up and out of the swamped basement to a nearby dumpster, we wondered — “Is this what it means to live in a climate crisis?”

Within the field of climate change communication, not all researchers support calling climate change a crisis. Some researchers warn that using extreme terms like “climate emergency” can reduce the credibility of news stories compared to those that call it “climate change,” or that this word choice simply doesn’t affect people that much. However, other research indicates framing climate concerns as an existential threat can generate strong emotions that motivate people to act on behalf of the environment. We hope using the term “climate crisis” can incite this pro-environmental attitude by accurately conveying the planet’s condition, and are encouraged by our analysis that shows the phrase’s uptick in usage.

This semester we worked with Charles A. Dana Professor of Political Science Erik Bleich as part of his Media Portrayals of Minorities Project, a research lab dedicated to analyzing newspaper article content to understand how media outlets cover pressing contemporary issues. Given our direct experience with local climate challenges, we focused on how the discussion of climate change has shifted over time. We analyzed 200,000 articles mentioning climate-related topics between 1980 to the end of 2023 from The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal and USA Today.

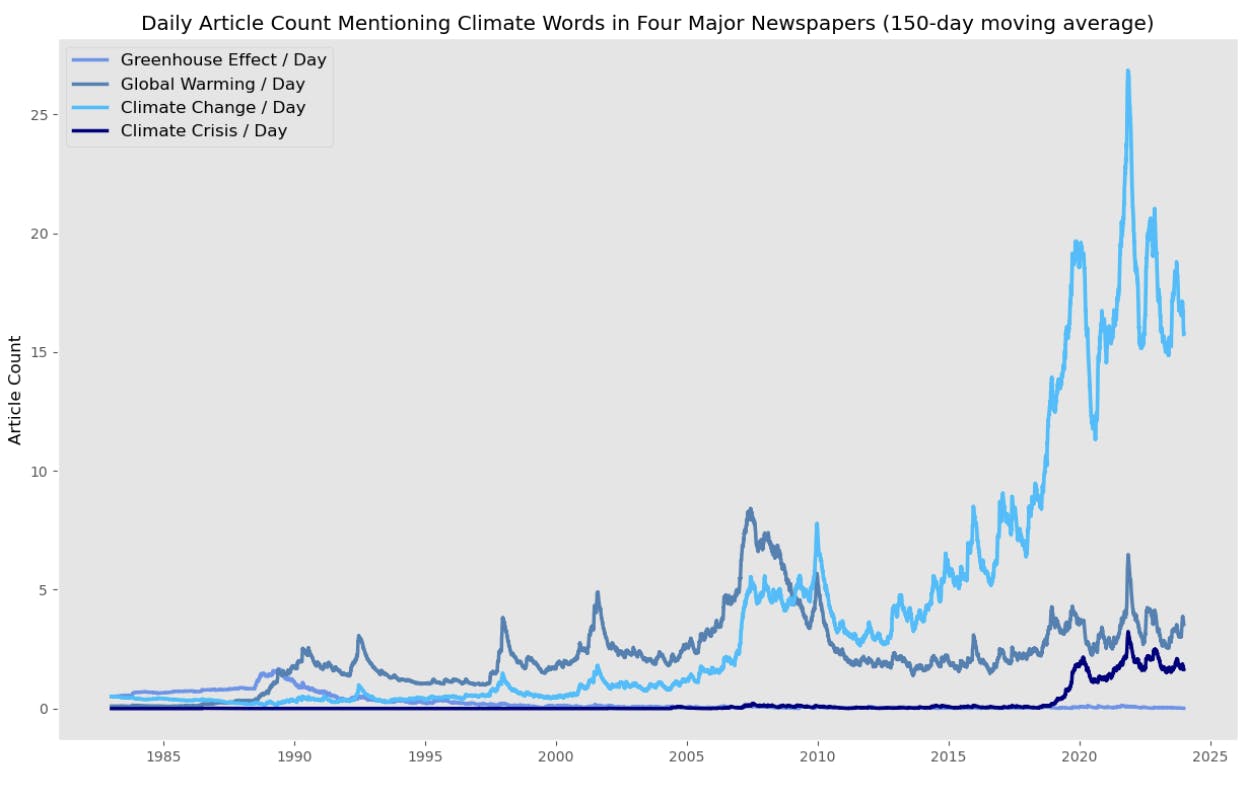

We found that newly introduced terms dominated the discussion. In the 1980s, the “greenhouse effect” was the most popular term, until “global warming” overtook it in the 1990s. Almost 20 years later in 2009, “climate change” surpassed “global warming” as the description of choice. As illustrated in the data graphic below, in late 2018 the media began using terms like “climate crisis” or “climate emergency,” which soon became almost as frequently used as global warming.

The rapid rise of terms such as “climate crisis,” “climate emergency” and “climate catastrophe” started regularly appearing in late 2018. During this time, Greta Thunberg launched her Fridays for Future campaign, which culminated in likely the largest climate protest in history in September 2019. Setting the tone for the public discussion that followed, she asserted in her December 2018 COP24 speech that “We cannot solve a crisis without treating it as a crisis.” Other activist organizations, such as the Sunrise Movement, also drew public attention. When they staged a high-profile protest outside then-House Minority leader Nancy Pelosi’s office in November of 2018, Pelosi responded by praising “the energy and activism of the many young activists and advocates leading the way on the climate crisis.”

These events — in addition to the 2020 presidential election’s heavy politicization of climate change — were discussed specifically in articles mentioning “climate crisis” most often after 2018, which suggests that they contributed to media outlets using this more extreme terminology.

When we shared our media findings with Middlebury College’s own Schumann Distinguished Scholar of Environmental Studies Bill McKibben, we discussed the potential risks in calling our situation a climate crisis. He told us that he’s not worried about being frank about the state of the planet, and asked rhetorically, “If you hear the fire alarm, do you give up, or do you turn on the hose?”

In the original Greek, a “crisis” meant a “turning point” rather than a devastating or paralyzing event. Our planet is experiencing the hottest temperatures on record; ice sheets are melting and sea levels are rising. Calling our situation a climate crisis accurately portrays the issue. But this label only helps when we view it as a turning point rather than the end of the road. Let’s look ahead toward a future filled with solutions and action instead of one with apathy and hopelessness. In doing so, we can set the stage for transformative climate action.