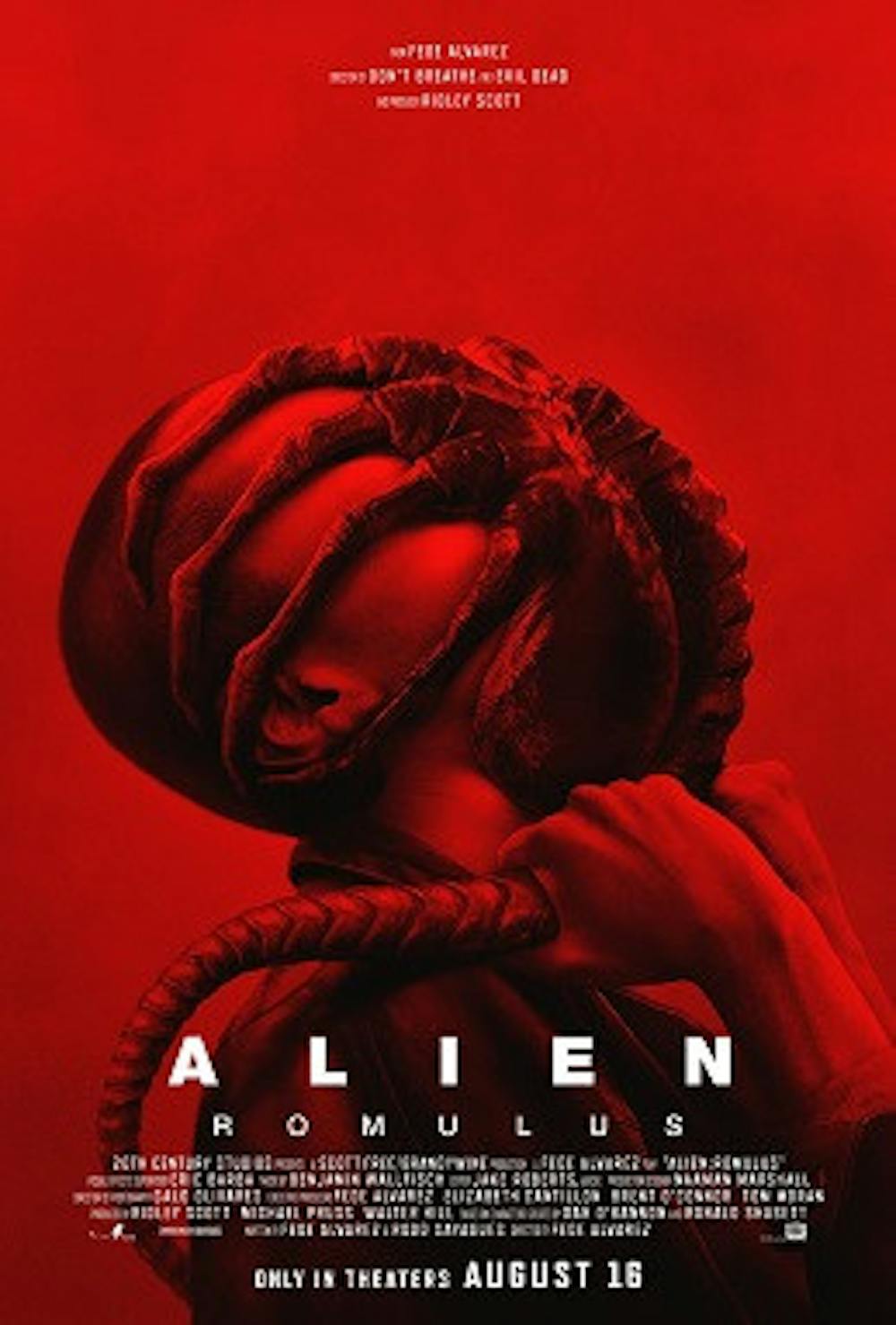

The newest addition to the “Alien” franchise hit theaters in August and serviced fans with a visually splendid but virtually unoriginal story. The film does, however, step out of its forebears’ shadow in one respect when it transforms the birth horror allegory of its predecessors into… actual birth horror.

“Alien: Romulus” is set in between the events of the original “Alien” (1979) and its sequel “Aliens” (1986). The film takes place in a mining colony and follows three sets of young siblings, all suffering under the oppressive circumstances of their indenture in the same mines that killed their parents. The plot takes off when Tyler (Archie Renaux) recruits the help of his ex-girlfriend Rain (Cailee Spaeny) and her android brother Andy (David Jonsson) to hijack a decommissioned space station and its cryosleep technology to escape to a distant planet. There, they accidentally awaken inert xenomorphs, the longtime antagonists in the “Alien” franchise. The group is rounded out by Tyler’s pregnant sister Kay (Isabela Merced), their cousin Bjorn (Spike Fearn) and his adoptive sister Navarro (Aileen Wu).

“Alien: Romulus” is largely an homage to the rest of the franchise and features stunning yet uninspired callbacks to the visual details of its beloved predecessors. Its one innovation is in anchoring the sexual allegory of the film’s inherited monsters to Kay’s pregnancy.

When “Alien” came out in 1979, it was hard to miss the flagrant subtext that linked the film’s monster —which, in its various forms, brutally penetrates, smothers, gestates in and rips open human bodies from the inside — to experiences like rape, pregnancy and birth. It served as a testament to the effectiveness of birth as an instrument for horror, capitalizing through immersive sensory imagery on the visceral — but largely unrealized — fear in male audiences of the violation of their bodily autonomy.

The initial creators of “Alien” solicited fear in male viewers by design. “That’s how I’m going to attack the audience; I’m going to attack them sexually. And I’m not going after the women in the audience, I’m going to attack the men. I’m going to put in every image I can think of to make the men in the audience cross their legs,’” Dan O’Bannon, the screenwriter for the original film, in the “Alien Saga Documentary,” (2002) said. It feels remarkable for a movie so male-dominated in its construction to have effectively neutered its own audience’s ‘male gaze,’ subverting an image that was typically a source of perverse pleasure when it happened to women and turning it into a source of pure horror by inflicting it upon a male character.

In a kind of double-reverse, “Alien: Romulus” builds on this creative tradition by attaching the film’s most potent and explicit birth horror imagery to a pregnant female character. From the moment that Kay confides in Rain about her pregnancy, the admission acts as a ticking explosive element in the plot, which waits to explode until the film’s third act.

Suffering from one of her numerous near-fatal injuries towards the end of the movie, Kay makes the desperate choice to inject herself with a serum that ‘perfects’ the human body using the DNA of the indestructible xenomorphs. The serum corrupts the young embryo and rapidly accelerates the gestation period resulting in Kay, minutes later, giving birth to a humongous xenomorph egg. The creature that sprouts from the egg is, admittedly, gloriously terrifying. It is approximately twelve feet tall and appears to be a human-xenomorph hybrid. The ‘Offspring,’ as it is called in the credits, is also meant to resemble characters called the Engineers, from “Prometheus” (2012).

The birth scene, on its own, is horrifying and grotesque. The image that follows, of the Offspring feeding from Kay’s limp corpse, is somehow even worse. It’s a visual motif foreshadowed earlier in the film, first by the allusion to the story of the twins Remus and Romulus (who traditionally are depicted suckling a she-wolf in their infancy) and the inclusion of the painting “View of the Hôtel de Ville of Marseille during the Plague of 1720” by Michel Serre. In the scene where Bjorn discovers the painting onboard the space station, the camera closes in on two of the figures in the foreground, a dead, gray woman sprawled on the floor and a young child feeding from her breast.

The final shot of Kay, discolored and literally sucked dry by her own ‘child’ is harrowing and its value in the narrative is nauseatingly impressive. It depicts the corrupting forces of the universe, untameable by even the most egregious capitalist greed, sapping the vulnerable human form of life itself.

This moment lingers in the viewer’s mind as the credits roll and colors the conclusion with an incredible, fitting… hollowness. Kay’s entire role within the movie, consisting of few lines and the brunt of the physical brutality, is sickeningly in keeping with her demise. . She is used, in her vulnerable form, as a punching bag for the film’s every symbolic blow.

It’s uncertain whether the creative decision to interpret the sexual imagery of the original works so literally and to use a woman as its vehicle is one to applaud or condemn. But viewing the two movies in their respective political contexts is discouraging, to say the least. “Alien” was released just six years after the passing of Roe v. Wade, the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case that, for 49 years, federally protected a pregnant person’s right to have an abortion if they so chose. Two summers ago, the case Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization rewrote that precedent. Since then, twenty-two state bans and restrictions on abortions have gone into effect.

We are living in a time in America where pregnancy and birth are topics that incite real fear and horror. And “Alien: Romulus” indicates that male artists and the major entertainment conglomerate they operate under might be too comfortable capitalizing on that fear. Art as an instrument for change is only effective when it challenges systems of power; when it makes those who are comfortable living in unjust times uncomfortable.

Unfortunately, the most interesting part of the movie is the irony with which it exploits female pain, hollowing out a subversive creative tradition, much in the fashion of its own antagonists.