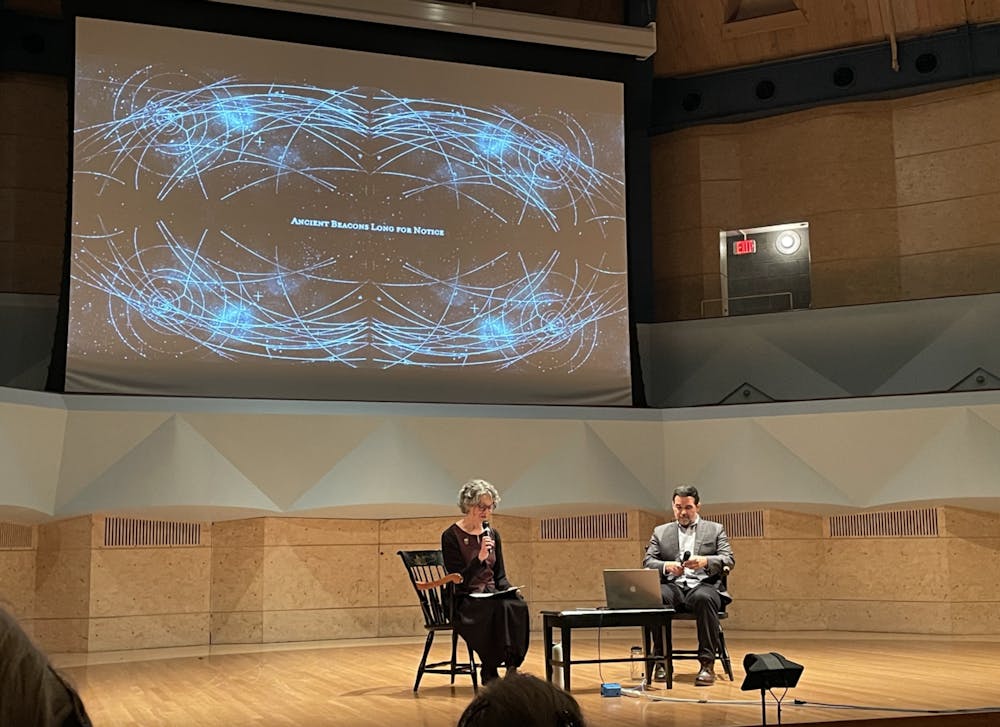

If you were to send a message into the great expanse of the universe, what would it be? Artist, writer and filmmaker Dario Robleto seeks to expand on this question in his film, “Ancient Beacons Long for Notice” which is currently on display in the exhibit, “An Invitation to Awe” at the Middlebury College Museum of Art. On Oct. 15, Associate Professor of History of Art and Architecture and “An Invitation to Awe” curator Katy Smith Abbott and Robleto had an insightful conversation about Robleto’s work and inspiration. The talk was sponsored by the Middlebury Museum of Art and History of Arts and Architecture department.

Based in Houston, Robleto’s work is a dedicated exploration of the interaction between arts, humanity and science. In past years, Robleto has accrued an impressive resume, working as a research consultant to the popular science television series “Cosmos: Possible Worlds” in 2020, and serving as Artist-At-Large in Northwestern University’s McCormick School of Engineering and the Block Museum of Art from 2018 to 2023. Currently, he is working on his first book, “The Heartbeat at the Edge of the Solar System: Science, Emotion, and Golden Record,” co-authored with Harvard art historian Jennifer Roberts.

Robleto’s film, “Ancient Beacons Long for Notice,” is the third in a trilogy, and is centered on the Voyager Golden Records. In his talk, Robleto elaborated on the fascinating story behind the Golden Records, shared his perspective on the kinship between art and science and reflected on the concept of “the lost awe.”

The conversation began with the story of the two Voyager spacecrafts launched by NASA in 1977. The Voyagers are space probes tasked with examining the edge of interstellar space.

“They transformed our understanding of the solar system, the place we called home,” Robleto stated in the talk.

Robleto found one of the Voyager’s missions particularly thought-provoking: in the hope that some outer space species may discover the Voyagers, scientists placed the Golden Records, a pair of identical phonograph records, onto the spacecraft. If properly interpreted, the Golden Records contain knowledge of almost everything about Earth and humanity through thoughtfully curated images, music, languages and natural sounds.

“For me, it was such a wonderful moment to reflect on because it was a rare moment where a scientific mission was issued in a poetic way, and that poetry came along with it,” Robleto said. “It was not easy. It was filled with hurdles and pitfalls, but they did it. They were beautiful attempts at a very strange problem.”

Robleto believes the member of the NASA team who helped create the Golden Records to be “one of the greatest artists that has not quite been acknowledged,” and that the whole film and the conversation is dedicated to her. This person, Ann Druyan, the only non-scientist on the team, posed the question to the NASA members: “What about love?” In other words, she touched on the moral question of humanity and eternity by the thought of adding human experience at an emotional level into the Golden Record.

On a trip to the Library of Congress, Ann Druyan discovered a World War One record made by Will Geizberg, the first recording ever made on the battlefield. Will Geizber died while making this recording; he breathed in toxic gas in the frontline. Moved by this experience, Druyan added an hour-long recording of EEG and EKG of her body onto the Golden Records. While making this recording, she thought of love —she was recently engaged at the time — and war.

“This is the Golden Record on the Golden Records,” said Robleto, “which made Golden Records one of the greatest arts that has never been recognized by art history.”

Nicoletta Coupe ’25 attended the talk and found Robleto’s work to blend visual art with other disciplines in imaginative ways.

“I found it really interesting that Robleto works with physicists, anthropologists, mathematicians, etc — his practice both pays homage to the literal work of Ann and Carl Sagan (the Record) and reproduces their working philosophy by blending these disciplines,” Coupe said in an interview with The Campus. “It feels so unlikely that, at the Golden Record’s inception, the team of scientists thought to include a singular artist and unlikelier still that a young Robleto found her work.”

Anny Druyan’s story inspired Robleto to think about the link between art and science. His creative process began with a simple question: If the “aliens” do contact us, what do we say back?

“I have asked many scientists the question and the answers are always physics, math…is that all? What about arts and music, the history of our invented ways to love each other?” Robleto said. “I believe that artists should be involved…especially in the way of what we say back [to the creatures we have never seen].”

In an email to The Campus, Smith Abbott described how Robleto’s film was a natural complement to the broader thematic structure of the “An Invitation to Awe” exhibit.

“The film is a natural complement to the scientific instruments in the Studio of Scientific Discovery, but it also has echoes in other parts of the exhibit: Acts of Humanity; Awe of the Tiny and Invisible (think of Ann Druyan’s EEG and EKG recordings that were compressed into barely more than a minute); and certainly the awe of sound,” Smith Abbott wrote.

Robleto finished the conversation between himself and Smith Abbott by making the following artist statement of the “lost awe.” “As an artist, I don’t want to forget that other thing that has happened [as awe] …that’s something I think I will solve in the future.”

Smith Abbott felt that, like Robleto’s film, their conversation was germane to the exhibit as a whole.

“Dario’s talk contributed to the exhibit in the same way his work does — by generating questions, getting us thinking, debating, reexamining what we thought we believed. He is a deeply thoughtful artist and writer and a wonderful collaborator,” she wrote.