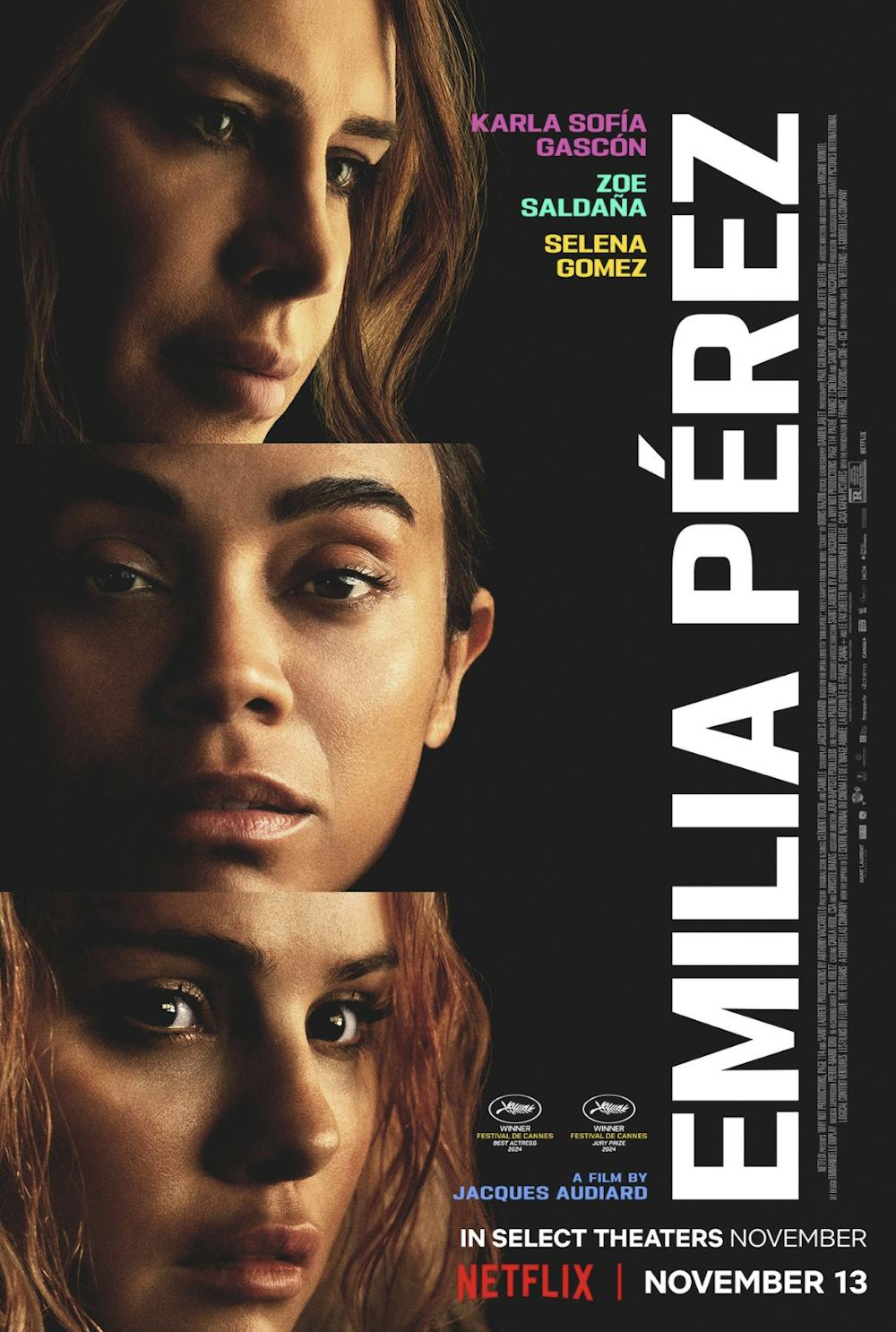

What strikes one most upon viewing “Emilia Pérez”, which first premiered at the Cannes Film Festival last May, is its resistance to description. The film, starring Karla Sofía Gascón in the titular role as a transgender woman looking to leave her life as a notorious cartel boss, uses conventions from several genres to create a proud mongrel of a film.

It is, at first, a crime movie — the story of a successful lawyer lured into corruption by Mexico’s robust drug scene. Soon after that, the film centers on Emilia’s coming-out story. Then the film skips four years and becomes a family drama, focusing on Emilia’s attempts to reconnect with her children. This plotline develops into a redemption narrative, which escalates into her creation of an non-governmental organization dedicated to the recovery of missing victims who were killed as a result of drug-related violence. Not only this, but the film is also a musical with operatic tendencies and complex choreography told in an unabashedly melodramatic tone. Needless to say, there is a lot going on in this film.

And herein lies the film’s greatest strength: its ambition. For an industry that has long depended on the replication of commercial successes as a mainstream production practice, it is refreshing to see work that prioritizes originality and innovation rather than mimicry (the film is, admittedly, an adaptation, but it’s only an expansion of a minor character in a recent novel, “Écoute” by Boris Razon). One cannot help but smile at the massive scope with which Audiard approaches this film. His outsized directorial imprint on the story exudes passion, care and respect for the medium and for the subject matter of Emilia’s journey and her overall redemption.

But it is Audiard’s same ambition that creates some of the biggest problems for “Emilia Pérez”. Too often the film tries to balance disparate genre conventions that, in the end, undermine the overall impact of the story. Emilia’s coming-out journey, for example, is framed with comedic undertones that clash with the dramatic importance of her story (i.e. by exploiting the contrast between the supposedly ‘masculine’ cartel boss and her desire to receive gender-affirming care as a woman). The moral dilemma Emilia faces — between abandoning her family and prioritizing her identity — and the aftermath of her decision cheapens the melodramatic tone of the film, which exposes Emilia’s inner life and, in turn, ignores the hidden guilt that would come as a result of that decision.

This is the same reason that the musical aspect of the film can sometimes feel unnatural; it tries to evoke the rich interiorities of the characters when subtext and silence could do more to impact the audience.

That is not to say that the film’s musical register fails entirely. There are many moments when the music, written by Clément Ducol and Camille, is able to create a sense of surrealism and achieve the operatic magnitude Audiard intended for the film (like in “El Mal”).

Combined with a sleek, dark color palette to both start and end the movie, “Pérez” effectively captures the rise and fall of the titular character in a Mexico that is reeling from the effects of drug trafficking and related violence.

This is ultimately where the film finds itself most compelling. Although “Emilia Pérez” is the story of one woman in and of herself, she also seems to represent something much greater. Her journey becomes symbolic of a larger cultural shift, one in which the individual and the collective must confront their pasts in order to build a more sustainable future.

Both Emilia and the state of Mexico experience a redemption throughout the film; just as Emilia commits to change and leaves behind a life of violence, the film’s representation of Mexico shows a country looking to amend the mistakes of its past. In this way, both Emilia the character and “Emilia” the film represent, first, a call to action and, second, a declaration of change in Mexico. It remains our job to listen up.