Antique clothing was dusted off and brought back to life this past J-Term in the “Historic Clothing Practicum,” co-taught by visiting Assistant Professor of Theatre Summer Lee Jack and Associate Professor of Costume Design at Penn State University Charlene Gross. The class focused on accessioning the college’s existing antique clothing collection, learning about textile degradation and preservation and curating a themed exhibition in Johnson Memorial Building.

Students separated into five stations: accessioning, which focused on cataloguing garments in a database; vacuuming, to keep dust and other contaminants off historic pieces; spot treatment, to address mold after bringing frozen garments to room temperature; and data information, which required students to research and practice "slow seeing" to garner extensive information on garments; and reference photography, where students took 360° views of the garments in front of a neutral grey drop.

Jack and Gross defined the idea of “close looking and slow seeing” by explaining how the longer and more closely you look at a historical garment, the more information you can discover from it. A stain, certain sleeve cut, faded label or the way the collar has shattered over the decades can reveal when and how the piece was made, which fabric it was made from and how it has disintegrated over time.

Middlebury’s antique clothing collection is comprised of over 400 historical garments. Some of the items were costume pieces used solely for plays, and costume design for historical plays at Middlebury often draws inspiration from the collection. Most of the pieces, however, were everyday clothing items worn by past Vermont inhabitants, the oldest of which is estimated to date from the early 19th century.

Historical textiles differ from other heritage objects in their casual everyday use, according to work by students in the class.

“Historical textiles… are vulnerable to damage not only due to their past history or composition, but also because they are familiar objects. As a result, historical textiles might have been handled more casually than other heritage objects,” a student in the class’ poster read.

However, it’s exactly due to the frequent handling of these items that we get to witness intimate marks left by people from the past.

This intimacy creates the tantalizing prospect of cross-temporal empathy, where we look at a piece of historical clothing in the present day and conjure a sense of the lives of those who once wore it.

“What people wore says so much about what they were like,” Gross said.

The work behind the course was not as concerned about restoration as it was about conservation, balancing the two major forces behind managing antique clothing. Oftentimes, time and resources had to go either into one or the other. It is refreshingly unconventional to explore the process of decay and disintegration when it is usually only the most well-preserved and glamorous items that are showcased.

The work of “dress detectives,” a term Lee coined, provides a deeper understanding into textile work and how it intersects with history and science. In understanding the process and cause of decay, entomology — the study of insects — plays an important role in differentiating between moth holes and carpet beetles. When trying to date a clothing item, historical knowledge plays a crucial part.

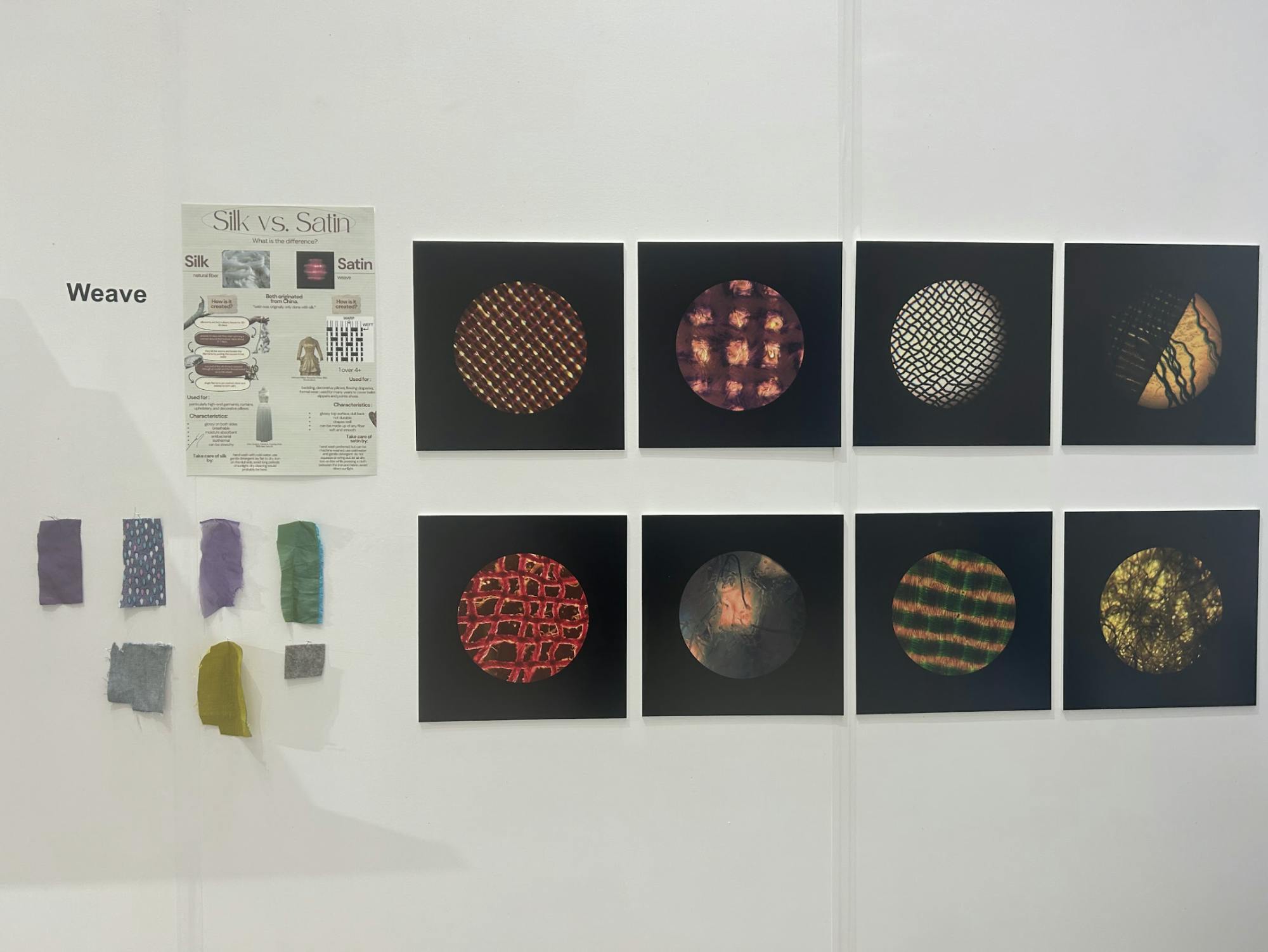

The class illustrated the multifaceted forces behind textile conservation and the creative potential of antique clothing. It is truly a testament to the fun-filled, hands-on and interdisciplinary focus of the J-Term experience. To learn more about the power behind textile work and antique clothing, visit Johnson Exhibition Gallery’s “Textile Conversations,” where students’ J-Term work is on display for the next month.