As the lights diminish, movement and prose skillfully unite. A dancer pirouettes through the stage in a red velvet dress as a voice narrates, “spinning, arms out, twirled like a reflection of a figure skater … 18, 19, 20 revolutions … arms out … Bronx sky … body in a perfect torso spin … chin-up, face forward.”

“This ghetto [is] getting gayer than Chelsea,” Charles Rice-Gonzalez said, closing his narration.

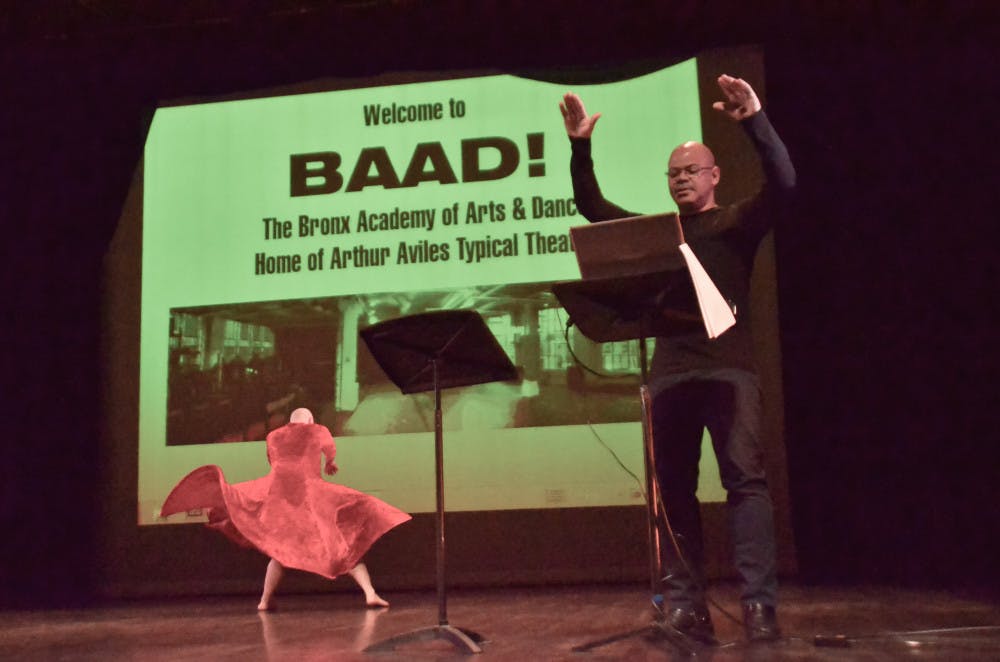

The union of art and community was the subject of a lecture-demonstration sponsored by Education in Action and Assistant Professor of Dance Christal Brown of the dance department. On Monday, Arthur Aviles and Rice-Gonzalez, co-founders of the Bronx Academy of Arts and Dance (BAAD!), delivered a message about opening your eyes and heart to both the thrill of the arts and the community that surrounds you.

In the case of Aviles, a dance choreographer, and Gonzalez, an author, BAAD! is located in the Hunts Point section of the South Bronx community, where Aviles and Gonzalez have laid down their roots to revitalize the neighborhood in the name of artistic diversity and vibrant culture. At the core, BAAD! is the live and pulsing intersection for people of many walks of life: gays, women, blacks, Latinos.

Social factors are fundamental to the expressivity of their art and BAAD!, Aviles said, is about the “legacy of performance, culture and dance.”

The lecture-demonstration began with a short documentary, “Hunts Point is Home,” to provide the audience with a context for BAAD!. Its message was that, as one interviewee said in the film, the United States is a place of the American Dream, but the Bronx culture is not part of the dream. There are no lights in Hunts Point, but activists like Aviles and Gonzalez are shedding light on the issue.

Forty percent of New York City’s garbage gets stored in Hunts Point. One Bronx resident said whereas the city sees the waterfront as a garbage facility, residents see that a park should be built. Another Bronx neighbor in the film said, “Trees clean air. Why do we only have one tree per acre?”

Hunts Point Riverside Park now exists as a gateway to the Bronx River, thanks to environmental activists in the neighborhood — namely gay members of the neighborhood who, Aviles said, organize themselves by community issues on housing and education — not sexuality.

The lecture segued into a demonstration of a technique Aviles created 10 years ago called “Swift Flow,” to speak to his dancers in a common language. In four movements —The Wave, Water Falls Into River, The Seaweed, The Swammy Mammy — Aviles taught this language to the spectators whom mirrored him in their seats.

And as it turns out, the “Swift Flow” transcends the common language shared between dancers to include people outside the studio and in the community in their experiment.

Aviles rolled the clip of himself performing the “Swift Flow” in a children’s park in the Bronx. At first, the children were playing a separate game of their own on the basketball court. Slowly, but then all at once, the children gravitate toward Aviles, mirroring his moves, and the scene looks as if he’s choreographing a class. This is an allegorical scene in which art strengthens and transforms communities.

Gonzalez and Aviles admit that they didn’t move into the South Bronx community with a mission statement. Instead, a mission statement arose from the experience of asking, “who is the artist?” or “who is the audience?” They understood what the people and the art looked like; they were women and queer. Audrey Lorde, Gonzalez recalled, insisted on being identified as “black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet.”

“I am all those things, all the time,” Gonzalez said, emulating Lorde. “Let’s embrace all our identities.”

With the philosophy of bringing arts back to the Bronx in mind, BAAD! provides workshop space as well as festivals for artists looking to perform. Every year, they host the BAADass Women’s Festival, a gay-lesbian-transvestite-transgendered festival according to Aviles, where artists showcase a suite of choreography, poetry and film performances. This year, they even offered a self-defense class called “Fight Like A Woman.”

“It’s got identity politics all over,” Aviles joked. “It’s exploding!”

In studio, BAAD! is a welcoming warm space. It is home to Aviles and his dance troupe, Typical Theatre. It is also a place of freedom to explore body and nudity in dance.

“The only limitations are that you don’t hurt anybody,” Gonzalez said. “The environment is whatever you want it to be.”

This is something to be said not only about BAAD!’s studio, but also about the greater community.

When a new person comes into the community, Aviles said, they need to collaborate with the community and ask the community what it is the community needs versus what they can offer. “You have to ask yourself: do you care about the place you’re in?” he said. “Why are you there? Who are you in this environment? Is it the good people you get to meet? Is it the buildings?”

“It’s valuable, not charity,” Gonzalez said. “I recall a time when I was writing an article for The Nation, my editor described Hunts Point as ‘a thumb jutting out in need of a bandage’ … but we changed it to ‘a rude child sticking out his tongue.’”

For Gonzalez, living in a community means listening and offering, it lies in value and respect. The dignity of Hunts Point can only be affirmed with collaboration.

Aviles admitted there are challenges in branching out to the community.

“We’re all outsiders to a certain extent,” he said. “We have distance within the community. We have both disconnectedness and connectedness and differences in perspective, sexuality, color, dynamics. [But] there is a difference between how it is to be there and how is it to do something there. Slowly and with great patience, we develop familiarity and relationships [with the community].”

To conclude, Brown pulled BAAD!’s narrative back to what it means to be a Middlebury College student.

“This is a story about bringing your whole self and being to your art,” she said. “I had an ulterior motive [when I brought BAAD! here], because it’s about the liberal arts experience as a living archive of giving students perspective on their dues.”

To that end, in visiting the College BAAD! sought to enlarge our insights on what it means to be a citizen of the world and expand our stage from our small community to the wide world.

Bronx Comes to Midd: Art Sets its Roots in Community

Comments