Choosing and beginning to use a new name is an important milestone in the transitioning process for many transgender individuals. For trans students at Middlebury, that process is complicated by the bureaucratic ordeal of navigating the college’s many online platforms.

In an ideal system, the preferred name and pronouns a student registers in BannerWeb would carry over to the college’s other online platforms. In reality, this information flows inconsistently and sometimes does not flow at all, making it incredibly difficult for trans students to fully transition at Middlebury, according to Director of Education for Equity and Inclusion Renee Wells.

Legal names — typically the name a person is given at birth — are those that appear on government-issued documents. Changing them can prove an expensive and arduous process, depending on the state. Many trans students have yet to change their legal name because of these difficulties and because doing so could require them to come out in ways they may not feel ready or safe to do. Preferred names refer to names some trans people choose as a way to better encapsulate their identity in the meantime.

Some platforms, like the students’ email accounts, automatically update once students change their names in BannerWeb. Others, like Canvas, require students to change their names on-site. Still others neither update from BannerWeb nor allow students to update them individually.

StarRez, which manages rooming assignments, falls into this category. Students often use the platform to see who their roommate will be, which can inadvertently out trans students, especially first years.

A.S. ’23 came out and began transitioning in high school, looking forward to a more “normal” college experience where he could live on a gendered floor and interact with people like his cisgender peers without having to be completely open or come out to everyone. Like many of his fellow first years, A.S. waited in nervous anticipation to find out his future roommate. When he checked StarRez and saw that he was listed with his legal name, that excitement turned to sickening dread as he realized that this stranger — whose attitudes were unknown and with whom he would be living in close quarters — already knew he was trans.

“I shouldn’t need to come out to anybody without making that decision for myself,” A.S. said. “But especially to people I live with and work with and who I just don’t know how they’ll handle it if they find out I’m trans. That, I think, is the most important recognition of privacy and responsibly using students' information.”

While other first years idly chatted and got to know each other in hall meetings, A.S. sideyed his roommate and first year counselor, wondering who exactly knew and what their reactions might be. While other first years nervously shifted in their seats during their first college classes, A.S. worried that his professors might inadvertently out him to the class during roll call. While other first years stressed about registration, making friends and forging their identities in this new environment, A.S. feared for his safety.

Students also cannot change their names on Presence, the platform student organizations use to take attendance, organize activities and manage their members. When student leaders search for students using their emails to add them to the organization’s page, they immediately see the students’ legal names. Presence outed A.S. to several peers against his will, uncomfortably expanding the network of people who know that he is trans.

The platform hosting the mail center’s data, the Center for Careers and Internships, and Advocate, the platform through which the college processes care and discipline reports, all fall into this category as well. This means that trans students often receive packages labeled by the mail center with their legal names or letters from the college addressed to their legal names.

Repeatedly facing their legal names and incorrect pronouns causes substantial harm to trans students, many of whom feel invalidated or stigmatized by these experiences, according to Wells.

For some trans students, seeing their legal name also brings up painful memories of family who do not accept who they are and weaponize their names to repeatedly reject their identity. This harm is compounded by the inconsistency of college platforms. Trans students never know when their legal name will appear and are often blindsided and unprepared for the harm it causes, according to Charlie R. ’21, president of Middlebury’s Trans Affinity Group.

The increasingly online world of the Covid-19 pandemic has only heightened the difficulties trans students typically face when changing their names and pronouns. Students inevitably have had to spend more time on online platforms both inside and outside the college system, forcing trans students to encounter their legal name more often, according to Charlie.

Correcting these issues often involves outing themselves to professors, classmates, administrators, human resources employees or Information and Technology Services (ITS) staff.

For example, CourseHub, one of the platforms that hosts class rosters, experiences problems with displaying trans students’ correct names and pronouns. In the past, it consistently failed to update students' names. Now it often lists students’ preferred names in parentheses after their legal name, according to Assistant Vice President and Chief Information Officer Vijay Menta.

Due to this set-up, professors who use these rosters to take attendance or call on students may misgender or use trans students’ legal names rather than their prefered names. This mismatch forces students to correct their professors, often in front of an entire class, effectively outing them as trans, according to Wells.

While medical, financial or student records often necessitate the use of legal names, many internal documents and interactions do not require them, even in these departments. Neither staff nor trans students have always received clear guidance on when they absolutely must use their legal name.

This uncertainty creates issues, especially regarding students’ health care. Appointments, emails and discussions between students and Middlebury’s various health care providers can legally occur under students’ preferred names but do not always, according to Wells.

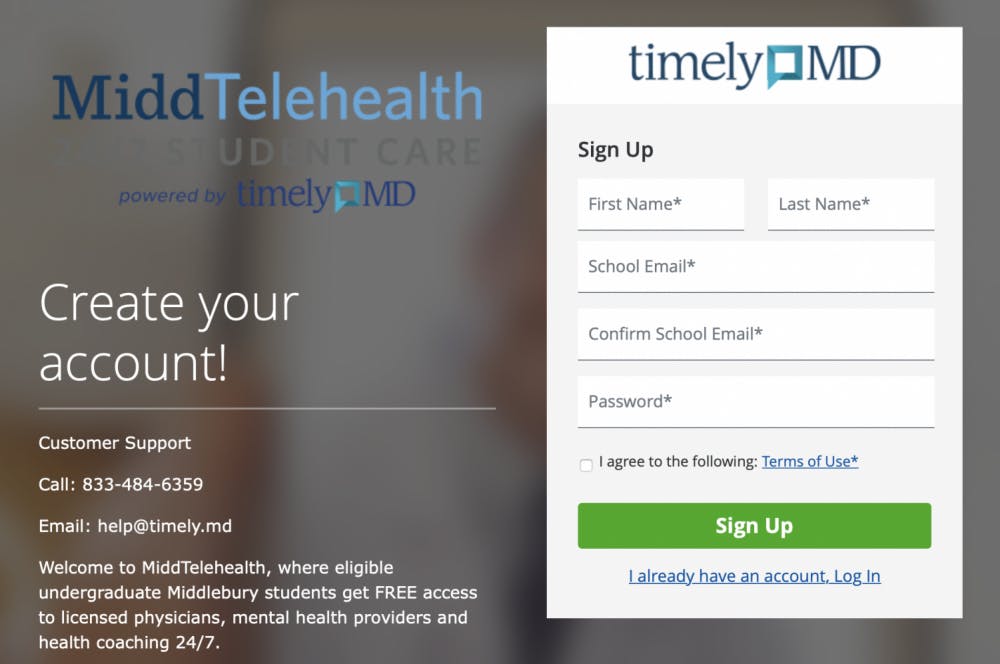

Francis S. ’23, who uses they/them pronouns, scheduled an appointment with MiddTelehealth this semester. Though they indicated their preferred name and pronouns when they created an account, their healthcare provider repeatedly misgendered them and wrote the appointment report using incorrect pronouns.

A month later, Francis arrived at Parton for their mandatory flu shot and identified themselves by their preferred name. When the medical provider couldn’t find their appointment, Francis had to introduce themselves by their legal name, an incident they say many of their trans friends also experienced.

Repeated instances of being misgendered or referred to by their legal names reinforce an oftentimes troubled relationship with healthcare and discourage trans students from seeking help when they need it, according to Charlie.

Parton currently requires that students identify themselves by their legal names at appointment check in, though the center plans to work with their electronic health record to alter this process in the future, according to Associate Executive Director of the Center for Health and Wellness Barbara McCall.

Health Services had never provided services on such a large scale before Covid-19 necessitated mandatory flu shots and was unprepared for the nuances of trans healthcare. McCall pledged to address this issue.

“Misgendering, deadnaming and other kinds of identity invalidation can significantly affect people’s relationships with medical and mental healthcare, including not seeking services when needed,” McCall wrote in an email to The Campus. “The Center for Health and Wellness is committed to on-going training, systems evaluation and the integration of student feedback to meet the healthcare needs of Middlebury students, including honoring and respecting their identities.”

Healthcare and financial platforms also are not required to display students’ legal names in their on-site interfacing, but many do anyway.

Each time Francis opens Oracle — the platform that hosts student employment payments, records and communication — they are greeted by a large banner on the top of the screen referring to them by their legal name. When Residential Life sent an internal roster to student employees, they pulled names from Oracle and listed Francis by their legal name, outing Francis to their supervisors and peers.

Some online platforms have internal information flow problems as well. Even after successfully changing their name and pronouns in Handshake, Francis still receives emails from the platform with subject lines like “[legal name], we think you’ll like these new opportunities.”

These display issues not only force trans students to confront their legal name more often, they create added stress as students worry their peers might see these sites or emails open on their computer.

A.S. remains constantly vigilant while navigating Middlebury’s platforms. Everytime he opens a problem platform or email, he looks over his shoulder to make sure he’s alone, and he never leaves those sites or emails open on an unattended computer or phone.

Even when college systems do allow trans students to change their name, they inconsistently display them. After updating their names in BannerWeb, some trans students’ emails and school directory listings continue to display their legal name and place their preferred name afterwards in parenthesis, as if it were a nickname.

Displays like those effectively out trans students with every email they send or recieve, especially when either their legal or preferred name carries a strong traditional association with one gender, according to Wells.

Because the college assumed that all of the systems for changing students’ names functioned correctly, no complete resource guide exists to guide trans students through the arduous process of changing their name throughout the many online platforms. Students must hunt down the individual instances where their legal name appears and attempt to change them one by one, Wells said.

Francis estimates that they have sent more than 10 emails to try to correct the name displayed in Oracle, to no avail.

"I had so many emails back and forth with HR that I just sort of gave up," Francis said. “It's really frustrating and demoralizing . . . [and] it takes a lot of time that I could be spending doing what I actually like doing. . . They see it as a minor inconvenience, but, for me, it's just another reminder that the world is hard for trans people.”

Many trans students also see the challenges they face while trying to change their name in Middlebury’s online systems as an indication that the college does not fully welcome or accept them. Every time Francis sees their legal name or has to correct someone, “it’s another reminder that [they’re] not exactly understood or safe [at Middlebury].”

That feeling of exclusion is even greater for students whose genders are not recognized by the college’s platforms at all. Students wishing to change their pronouns in BannerWeb are only given three options: he/him/his, she/her/hers and they/them/theirs. These options exclude genderfluid, bigender, demigender and agender students, among others, as well as those who use neopronouns like xe/xem/xyr.

“The institution needs to create space for people and affirm people,” she said. “When we're sending out messages that are invalidating them, we're doing the opposite of that… It creates a lot of harm that's being done by the institution that you've chosen to make your home for four years.”

This year, Digital Learning and Inquiry (DLINQ) added pronoun options to Canvas, which will display alongside students’ names on the class roster, discussion posts and other interactions. Students whose preferred pronouns are not included in the drop-down menu can submit a consultation request form to customize their pronouns, according to Heather Stafford, a DLINQ instructional designer.

Wells approached ITS in the fall of 2019 to resolve these issues across Middlebury’s various online platforms. According to Menta, ITS has since made some small strides towards fixing the many problems, including creating space in CourseHub to display students’ preferred names and pronouns, but much of the problem remains unresolved.

“There is no unilateral fix that will resolve all the existing errors,” Menta said. “There are many systems that need to be coordinated and important issues of accessibility and security to be considered as we make changes.”

ITS’s former project manager got as far as addressing some small issues and identifying the key problems before he left in January. Unfortunately, the department has been unable to hire his replacement since the college instituted a hiring freeze last spring, and the project fell by the wayside. ITS is committed to addressing this issue “as soon as the pandemic is behind us,” according to Menta.

Trans students who are currently forced to navigate the inadequate name-changing system are dissatisfied by Middlebury’s long-term approach to fixing it.

“I totally understand that people are spread thin right now, but students still deserve to see their real names (not their given names) on Middlebury platforms,” Francis wrote in an email to The Campus. “When a friend comes to me saying that they want to change their name in Midd's systems, I hate having to tell them that it's an uphill, often impossible battle.”

While trans students wait for an institutional fix, they must rely on each other for help navigating this process. For some students, the Trans Affinity Group fills the holes left by the lack of institutional support. Trans students use the meeting space and group chat to troubleshoot the process of changing their name across college systems, spitball name suggestions for transitioning students and provide a safe space and support as they attempt to navigate a college that does not always accommodate or prioritize their needs.

“Being trans is beautiful. Being trans is fantastic. Transitioning is hard but has wonderful outcomes,” Francis said. “But [difficulties with updating my name on college platforms] are still a reminder that institutions...are not set up to make sense of who I am.”

Editor’s note: Some interviewees have been granted partial anonymity for their own future privacy and protection. A.S. ’23 is a member of The Campus’ staff.

Trans students seeking support can reach Charlie R., president of the Trans Affinity Group, at crouhandeh@middlebury.edu.

Sophia McDermott-Hughes ’23.5 (they/them) is an editor at large.

They previously served as a news editor and senior news writer.

McDermott-Hughes is a joint Arabic and anthropology and Arabic major.

Over the summer, they worked as a general assignment reporter at Morocco World News, the main English-language paper in Morocco.

In the summer of 2021 they reported for statewide digital newspaper VTDigger, focusing on issues relating to migrant workers and immigration.

In 2018 and 2019, McDermott-Hughes worked as a reporter on the Since Parkland Project, a partnership with the Trace and the Miami Herald, which chronicled the lives of the more than 1,200 children killed by gun violence in the United States in the year since the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Florida.

Olivia Mueller '24 (she/her) is a News Editor.

Previously an Arts and Culture editor, Olivia is an International Politics and Economics major with a Spanish minor. Outside of the Campus, she is a spin instructor for YouPower, an avid runner and hiker, and a member of the Middlebury Mischords a cappella group.