In honor of my final contribution to the Campus, I wanted to mention some things I love about Middlebury. I love that everybody is on the same housing and meal plan. I love that we all have access to top-notch athletic facilities, to mental and physical health services, and to innumerable devices and software. I love that students started Middbeat, JusTalks, beyond the green and Womp. I love that we’ve got need-blind admission (if imperfect). We’ve got major problems at Middlebury, but for these (and other) reasons, Middlebury is arguably more inclusive to its members than American society as a whole. What these things share in common is the commitment to equity amongst students.

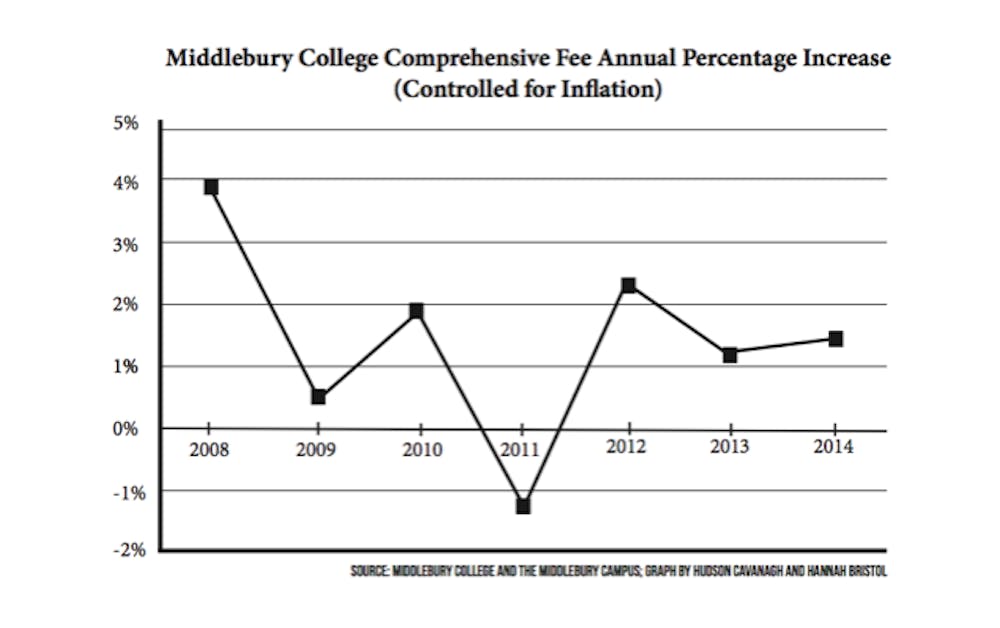

We should be celebrating rising tuition in the same spirit. Tuition that rises faster than inflation is not a bad thing; in fact, I believe our tuition should rise faster than it does now. It would be a key piece of one of the most inclusive policies that our college can choose to adopt.

To clarify, rising public college tuition is not only a force that is exacerbating systematic inequality, but the accumulation of student debt is a major macro-economic problem in the United States. Rising tuition at state universities around the United States is a major obstacle to our nation’s economic competitiveness; it restricts upward mobility and squeezes the middle class. Protesting public tuition hikes is well founded.

But in the decade before 2012, the total annual cost of college (defined as tuition plus room and board, controlling for inflation) increased 40 percent for public schools, compared to only 28 percent for private non-profits. From 2004-2012, 71 percent of Americans lived in states where public school total costs grew faster than private schools. This is harmful: as the economy grows private school rates would ideally rise to accommodate increasing proportions of qualified, upwardly mobile, aid-dependent students, while public school rates should decrease to expand access, especially in times of economic distress. We can’t control public tuition, but we should strive to absorb the very best students who are squeezed by the system.

A private, non-profit institution like Middlebury is different from state universities, most relevantly, because the government cannot impose different prices for the same good depending on the individual payer. The government may be able to tax as it sees fit, but it cannot charge rich people more for stamps. In contrast, as a private non-profit institution, Middlebury can, in effect, charge different rates because of our commitment to “meet demonstrated need.” Arising from that commitment, charging a higher “sticker” tuition price (which only 58 percent of students actually pay) would function as a progressive tax that would free an enormous amount of grant aid funding.

Financial aid comes at a great cost, but is absolutely fundamental to our community. The Board of Trustees increased the total cost of college 2.94 percent for this upcoming year, but if that number had been 5.00 percent, we would free enough money for the provision of “average” aid grants to more than 28 students. Demonstrated need would still apply: anybody who could not foot the tuition increase could be covered with freed funds. Those that could afford full sticker price would pay, roughly, an additional $2,900 per semester; given the wealth of many Middlebury students, this is a small price to pay for admission to one of the best liberal schools in the world. Indeed, many families gracefully give beyond tuition costs as alumni donors. Half of applicants would pay no increase in price. This is an example, not a prescription: I do not know the ideal rate, but I believe growth in tuition costs should increase more than it currently is. I’m not advocating any other use for tuition hikes, nor am I opposed to other sources of funding for student aid; my point is we can improve the system meaningfully at the margins.

Frankly, many Middlebury students get in every year because they have money. I am a good example. I got into Middlebury off the waitlist — the fourth student from my private high school class of 80 — and part of it was because my family could pay sticker price. Increasing “sticker price” could end our need-blind-except-for-the-waitlist policy and bring greater socioeconomic diversity to campus.

Based on the amount of people who have shared experiences of marginalization based on race and class — which have been widely expressed in public forums — increasing need-based student aid could help Middlebury’s ability to attract a critical mass of identity groups to campus. Students here should not have to be representatives of their entire race in classrooms and parties, and Middlebury should not be as overwhelmingly white as it is. Most importantly, we could attract more of the top students who cannot pay their way to Middlebury.

I respect Middlebury as an institution. I value the people I met here as highly as anything. We should welcome this reform — despite the cost — for the betterment of the college that will always be my Alma Mater.

Why We Should Raise Tuition

Comments