When Courtenay Roche arrived on campus as a first-year in the spring of 2017, she began to develop an unhealthy relationship with food and exercise. The problem worsened throughout her first two years of college, and Roche recalled having less and less energy to devote to friends and extracurricular activities.

“Because I wasn’t at home, I was more easily able to engage in bad behaviors that my parents would not have let happen,” she said. “Middlebury is a very isolating place. It was very easy to suffer in silence.”

Roche withdrew from school in the fall of 2018 and sought treatment. Once her recovery process was underway, she decided not to return to Middlebury at all. While her decision to transfer was driven by a number of factors, Roche said that Middlebury’s culture around dieting and exercise contributed to her desire to leave.

Middlebury can be a difficult place for students who struggle with body image and eating issues. Some students enter college with a history of disordered eating while others develop new unhealthy habits on campus, but many who need help often find on campus expectations about exercise and body types harmful and the college’s mental health resources insufficient.

While students spend a lot of time focusing on often-skewed ideas about “healthy” eating and the importance of exercise, there is very little conversation around what happens when those norms go unchecked. Despite the fact that students every year must leave to seek intensive treatment, there is not a common understanding of eating disorders on campus. Eating disorders can impact people of all genders, races, socio-economic backgrounds and ages. In addition to those with formal diagnoses, many students experience “disordered eating,” a term used to describe a range of irregular eating behaviors that may or may not warrant a specific diagnosis.

For many students, the way peers talk about food and beauty standards creates unhealthy expectations regarding body appearance. Abby Blyler ’19.5 began struggling with an eating disorder the summer before high school. She feels that Middlebury amplifies harmful standards about body size.

“Our culture is so fatphobic and I think that’s hyperprevelant here,” she said.

Blyler, who left campus to attend a residential treatment program last fall, said this can manifest in conversations between students about how much they eat and exercise, or comments that frame food as a reward for exercise rather than a daily necessity.

Quinn Boyle ’21, who recently wrote a widely shared op-ed in The Campus about her experience, said that for her, coming to Middlebury exacerbated an issue with which she was already struggling.

“Middlebury has a very perfectionist culture, and because society believes that skinny bodies are perfect and fit bodies are perfect, not only do we want to do 110% in our academics and extracurriculars but we want to do 110% when it comes to the way we look,” she said. “I got really sucked into that.”

Many students said structural factors can make college challenging for students with eating disorders. This includes having to navigate dining halls, where the public nature of eating and food can be an issue, according to Boyle.

“I was really socially isolated,” she said. “I couldn’t really do meals with people, I either ate in the dining hall alone or I ate in my room and I lost a lot of friends. It was really horrible.”

A lack of resources for mental health

The counseling staff at Parton Health and Wellness Center are generalists — they are able to help students who struggle with disordered eating until the issue has reached a certain level of severity, according to Gus Jordan, the executive director of health and counseling services.

“We treat eating disorders very much like we do any serious medical or mental health issue,” he said. “Last summer, I had all our staff go through a day-long eating disorder training with two specialists from a clinic in Boston.”

Jordan explained that part of the training was geared toward assessing whether students need more support than therapy every other week can provide. For students experiencing more severe symptoms, the college may not be able to offer sufficient care to help them start or continue recovery.

The level of care the college is able to provide to students has been impacted by a surge in students seeking mental health services on campus, The Campus reported last spring. Jordan said that demand has risen drastically in just a few years, which reflects a larger national trend.

“Five years ago we were capable of seeing every student who wanted care weekly,” he said. “We now have difficulty providing every other week therapy. My staff are carrying caseloads that are twice the size as they were five years ago in trying to manage all the people that are looking for care.”

This shortage of counselors means students who need more regular therapy to treat an eating disorder might not be able to schedule appointments frequently enough to help them. In the long term, Jordan explained, this kind of under-treatment can do more harm than good for people struggling.

“If you provide inadequate or too low a level of care relative to the severity of the condition, what you’re doing is you’re helping the student practice their eating disorder without it getting better,” he said. “In other words, if I’m providing once a week therapy, or every other week therapy, to a person who really needs intensive outpatient treatment, then they may be using the therapy to keep their head above water while they are practicing their eating disorder and so they are actually getting worse during that time.”

The lack of resources on campus leads some students to seek solutions elsewhere. However, in a rural setting like Addison County, the options around the college are also limited.

[pullquote speaker="Gus Jordan" photo="" align="center" background="on" border="all" shadow="on"]Middlebury students say that the college’s culture contributes to unhealthy expectations around food and exercise, and that the resources for struggling students are lacking.[/pullquote]

Amy Rice, a local dietician who frequently works with Middlebury students who have eating disorders, said that it can be challenging for patients to assemble the team they need, which usually includes a dietician, a therapist and a doctor. Rice explained that there are more options and more variation for those seeking care in the Burlington area, but traveling an hour each way for multiple appointments a week is often an unrealistic option for Middlebury students, especially for those without access to transportation.

Receiving care from professionals in town can also come with a hefty price tag.

“It was so hard to find people that would take my insurance,” Boyle said. “Being on the school’s insurance means that most people are not in-network with whatever health plan Middlebury provides. So then going through the process of talking to your insurance companies and then talking to your provider like your therapist or your dietician and coming up with a number you can actually meet is super difficult and stressful, and on top of that you still have to pay money out of pocket.”

Boyle and other students interviewed for this article expressed a desire that the college hire more specialists, such as a nutritionist or specialized eating disorder counselor.

Jordan said he also hopes to one day have a nutritionist at the Parton, either as a full time staff member or on a part-time basis. He explained that there was a part time nutritionist at Parton in the early 2000s, but very few students made appointments so the college decided to redirect funds used for the position elsewhere.

“But that doesn’t mean it wouldn’t work now,” he said, pointing to the increase in the overall use of mental health services since then.

Boyle said access to a nutritionist on campus would be a good first step. She also believes the college should hire or bring in a specialist to run a support group for students who are struggling with disordered eating.

Eating disorders and athletics

While eating disorders impact students across campus, being an athlete can present unique challenges for students trying to recover. This is especially true for students with teammates who struggle with similar issues. Blyler plays for the women’s soccer team, and said that in her experience, the environment on sports teams does not always facilitate healthy habits.

“Every season I have overheard or witnessed teammates expressing the desire to lose weight, become more toned or go on a new fad diet. You have people eating a Proctor bowl worth of food for their whole dinner,” she said. “To me, that just shows how little education there is around health and wellness. We live in such an active community, we need to be properly fueling ourselves.”

Part of the problem, Blyler said, is that teammates do not always talk openly about the issue.

“People don’t want to say, ‘I had an eating disorder.’ Instead you see what they eat,” she said. “Teams have meals together all the time. So you’re just like, ‘Oh my god she’s eating just a salad, should I be eating that?’ Especially for people who may have a greater tendency to fall into that stuff it’s such a slippery slope.”

Rory Kelly ’19, who ran for the cross country and track and field teams while in recovery from an eating disorder, said that being an athlete changed her relationship to her recovery process.

“There were a lot of toxic things going on about food and body image on both the men’s and women’s teams,” she said. “I was in a lot of conversations about mental toughness and being kind to yourself and pushing yourself and where that line is.”

For athletes struggling with eating, there is often little their coaches and trainers can do to help them. While many coaches are aware this issue exists for their athletes and want to help, there are few resources for coaches to learn how to approach this topic. Kelly said this problem goes beyond Middlebury and exists in sports at large.

“There’s no good training out there for coaches on how to step in,” she said. “[Our team] did feel comfortable talking about how to get faster, but balancing taking care of ourselves and also doing that thing called school .... The area that’s still lacking is in the moment [when someone is struggling], you have to buck up and step in and have a difficult conversation.”

Nicole Wilkerson, the head coach for both the men’s and women’s cross country teams, expressed frustration with the lack of information available to coaches about how to help an athlete struggling with an eating disorder. In the past, Wilkerson has brought speakers in to help educate her team on this issue and how to take care of themselves. But she said that when it comes to specific cases, it is hard to know what to do.

“There’s not a clear avenue to say hey you need to do x, y and z in order to be able to compete, in order to return to practice,” she said. “It’s just trying to tackle this on our own.”

According to Blyler, athletes often worry that if they tell their coaches about their eating disorder, they will be benched — or that if they start the recovery process in season, it will hinder their performance.

“How do you navigate healing and navigate getting help when you don’t necessarily feel like you need to get treatment, and you’re in the middle of a season, and you’re trying to outcompete your peers? How do you do all that?” she said.

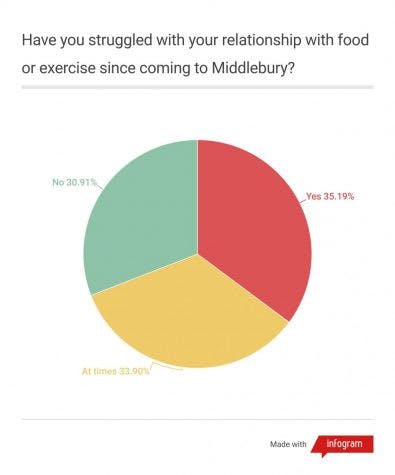

In this year’s Zeitgeist survey, nearly 70% of students reported having some struggles with eating or exercise during their time at Middlebury.

The cost of leaving for help

The help Parton can provide to struggling students includes weigh-ins — regular appointments to check if a student gaining or losing weight in relation to medical recommendations. However, Jordan said that the health center cannot guarantee the accuracy of the results, given that students are not monitored to ensure they are not tricking the scale like they may be at a facility that specializes in treating eating disorders.

If a student appears to be at risk of serious health consequences from their eating disorder, counselors at Parton will start talking with students about taking a leave of absence.

“We take action when there is imminent risk to a person,” he said. “That’s when we ask and say, ‘you might have to go home.’ We might involve parents or a dean.”

Rice said that for students facing worsening symptoms, she believes it is often better to take time off and get more help than Middlebury and the surrounding area are able to provide.

“If they need those bigger centers or that higher level of care the question becomes is it in their best interest, is it better for them to take a semester off versus struggle trying to manage college and their eating disorder for the duration of their college experience?” she said.

For students, the decision to leave can be an incredibly difficult one. Many expressed that they reached rock bottom before they were willing to admit they needed to seek more intensive treatment. Blyler reached that point last November.

“It got to the point where it was infringing on my everyday. I couldn’t do school work,” Blyler said. “I was sleeping through so many things and I was socially isolating and trying to hide it from everyone.”

For Blyler, the decision to leave school came with significant financial implications, which is the case for many students contemplating a medical leave of absence for residential treatment. In addition to potential loss of tuition money for the semester a student withdraws, treatment programs for eating disorders can cost tens of thousands of dollars a month.

Blyler was able to negotiate for her college insurance plan to pay for 90% of her treatment last fall, but that still left her with a $6,000 bill.

“I was like, I don’t have that,” she said. “My parents aren’t financially involved – they don’t pay for anything and I have to pay for college, too.”

Blyler ultimately received a grant from a foundation to cover the rest of her treatment.

Boyle’s situation was also complicated. Her family cannot afford the cost of treatment, and Boyle said that she would not be able to recover living at home, leaving her with very limited options. Boyle said that she was ultimately able to access treatment because a friend’s family took her in and paid her medical expenses.

“I’m really lucky that this family is giving me financial support right now, if they were not I would not be able to get any help whatsoever,” she said. “I could have died if they hadn’t been there. It was so bad.”

Boyle also expressed frustration that she had not been able to access more regular therapy and appropriate medical treatment earlier, while she was still on campus, which she feels may have kept her disorder from worsening like it did.

“It’s really shameful that Middlebury does not provide those resources,” she said. “Not only does it set kids back mentally but it sets you back financially and it makes it way harder for you to recover and it really does disproportionately affect kids from low incomes who can’t support themselves or don’t have family to support them.”

After spending several months in treatment, Boyle recently re-applied to be allowed to come back to Middlebury for the spring, and last week she was given permission to return.

“I’m not cured by any means but I’m better than I’ve been,” she said. “Middlebury provides routine, it provides stability, it provides a home where I feel like I belong, and I have an entire treatment team currently in Vermont.”

She hopes that Middlebury will take steps to change the culture on campus and make more resources available to students.

Jordan said one thing he believes the school can do to help combat the broader problem is institute more preventative measures. He feels that educational programming through the Health and Wellness Office will have a positive impact on campus culture.

“To me that’s where the energy needs to go because I don’t think we can treat ourselves out of these situations,” he said. “We need to do much more preventative work.”

Blyler said that one of the best things students can do is destigmatize eating disorders and learn how to talk about them responsibly.

“It needs to be not so taboo because I know so many people who are so afraid to talk about it,” she said. “[But] if you pick five random people on this campus they will all say at one point in their life they have struggled with this to some extent.”